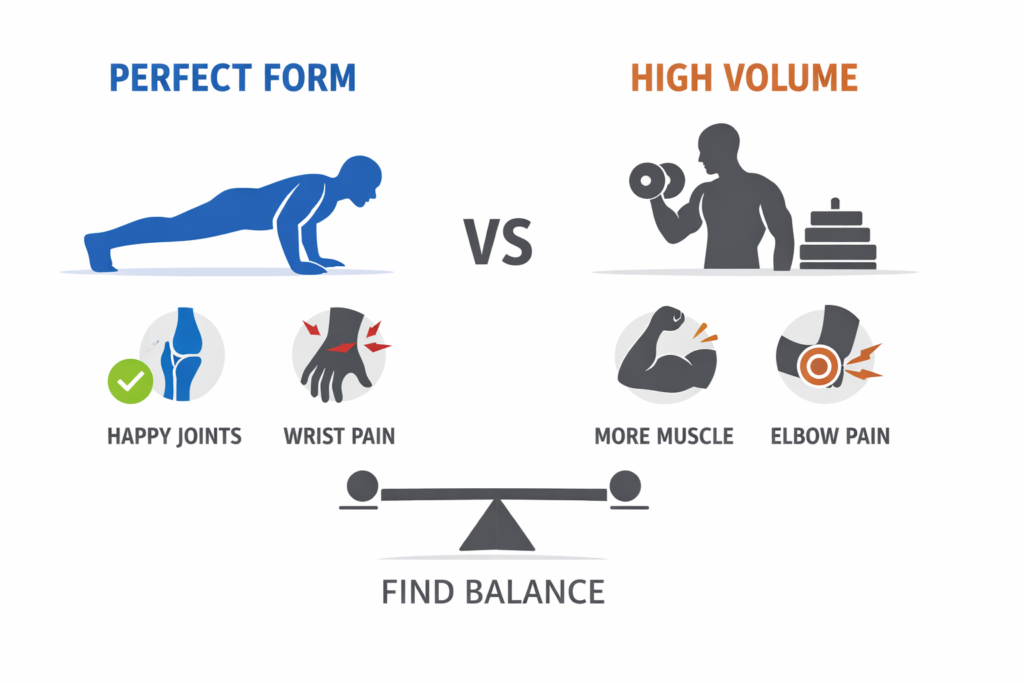

I Trained With Perfect Form, Then With High Volume — Here’s What Hurt (and What Didn’t)

Two loud opinions kept popping up across the fitness world. On one side, perfect form was treated like a software update that magically fixes everything. Across the room, another camp insisted volume was the real engine, and technique only needed to be “good enough.” Instead of arguing with imaginary people in my head, I decided […]

I Trained With Perfect Form, Then With High Volume — Here’s What Hurt (and What Didn’t) Read More »