You know how it goes.

You start doing your usual wide grip pull-ups, and everything feels fine.

You’re feeling strong, the movement is smooth, your body’s responding well.

Then suddenly, maybe after the second set… zap.

A weird twinge, right inside your elbow.

It’s not exactly painful, but it’s definitely annoying.

Like something’s not gliding the way it should.

It’s not your usual bicep soreness.

It’s not even back fatigue.

It’s something more “hidden.”

And every time you pull—there it is again.

More persistent. More frustrating.

Welcome to the club of people who pissed off their brachialis without even knowing it.

My ordeal with the brachialis (and how I got out of it)

I’ve been through it too.

I had a mental obsession with wide grip pull-ups.

They looked cool.

They made me feel like an “athlete.”

And hey, not everyone does them.

But after a month of daily wide grip pull-ups…

My right elbow started acting up.

I couldn’t even lift the kettle without wincing.

I completely stopped for two weeks.

Then I restarted with:

- Supinated pull-ups

- Neutral grip ring pull-ups

- Forearm and grip strengthening exercises

And within four weeks, the pain was gone.

I never forced wide grip pull-ups again.

Only when it made sense. Only when my body was ready.

Who is this muscle no one ever talks about?

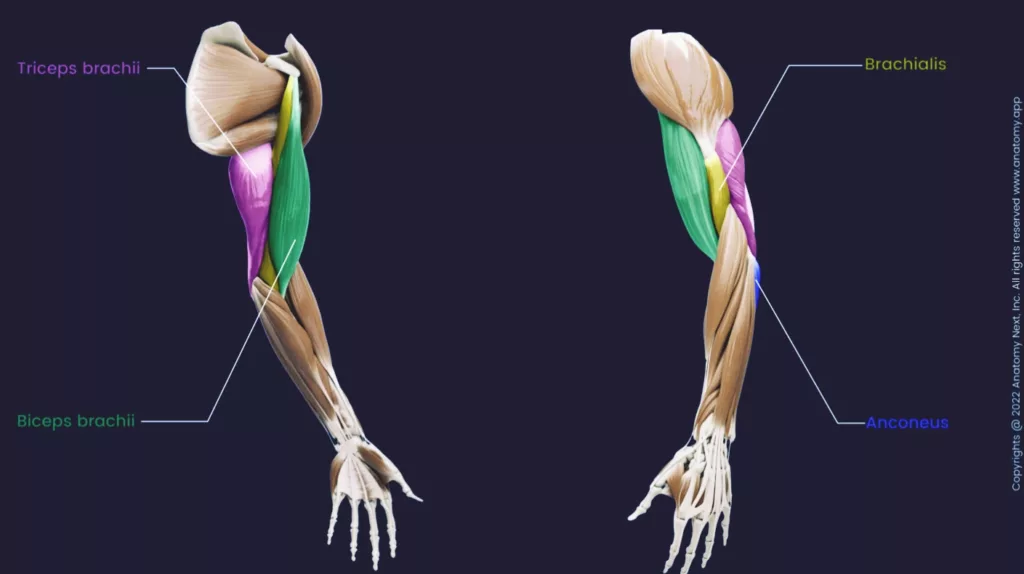

The brachialis is your classic silent worker.

It sits underneath your bicep and does the bulk of the work anytime you flex your elbow.

Unlike the bicep—which is like the reality show star of muscles (wants attention, lights, poses, and a pump)—the brachialis is all business.

It works hard.

It doesn’t complain.

Until you push it too far.

It’s involved in almost every pulling motion, especially when your palm is facing forward or down (like in pronated or neutral pull-ups).

And that’s where the problems begin.

Why wide grip pull-ups can be a trap for the brachialis

In theory, wide grip pull-ups are supposed to target your lats more.

And that’s valid.

By widening your grip, you reduce bicep involvement and “isolate” your back.

The problem?

Biomechanical nightmare.

When you spread your hands too wide, your shoulders are forced into external rotation.

Your elbows flare outward.

And you’re asking your poor brachialis to flex your elbow from an awkward, stressed, and totally unnatural position.

It’s like asking someone to shovel snow with the shovel flipped backward.

He can do it… but you’re going to wreck him in the long run.

Especially if you train with high volume, like many do in calisthenics.

10, 15, 20 reps per set.

Maybe even weighted.

Maybe every single session.

Meanwhile, your brachialis is crying out for help.

But you’re not listening.

Until it actually starts to hurt.

How to recognize brachialis pain (without confusing it for something else)

Brachialis pain isn’t the “good kind” of pain—like post-workout DOMS.

It’s more pinpointed, more irritating, and it doesn’t go away with stretching.

Here’s where you might feel it:

- Front of the elbow

- Along the top side of the forearm

- When you fully extend your arm after training

- Or… when opening a jar feels like you’ve got the arm of a 90-year-old

Sometimes it only kicks in when lowering yourself from a pull-up.

Other times you feel it even at rest—like a deep ache or tingling.

And the risk is that it escalates.

First inflammation.

Then tendinitis.

Then you’re forced to quit pull-ups. And that’s when you really start cursing.

Why calisthenics can make it worse if you never rotate your exercises

One of the beautiful things about calisthenics is the simplicity.

Bar.

Bodyweight.

Gravity.

But that same simplicity becomes a double-edged sword when it comes to overuse injuries.

If you’re the kind of person who only does classic wide grip pull-ups—never changing grip, angle, or stimulus…

You’re cooking up a lovely omelet of inflamed tendons.

In the gym, you can switch machines, use dumbbells, cables, different angles.

In calisthenics, it’s you and the bar.

And if you don’t mix up grips and movement patterns smartly, your brachialis is one of the first to send you the bill.

What you can do to save (and strengthen) your brachialis

If you feel inflammation, stop immediately.

Training through pain won’t make you tougher—it’ll just make you more broken.

Then, follow these steps:

- Swap wide grip pull-ups for neutral grip pull-ups (palms facing each other): much easier on the elbows.

- Add supinated pull-ups (chin-ups) to offload the brachialis and engage the biceps more.

- Do horizontal pulling work (like inverted rows, ring rows, Australian pull-ups) to give your elbow flexors a break.

- Use a lacrosse ball to massage the brachialis (just above the elbow) and release tension.

- Train eccentric strength—maybe with bands or slow, controlled reps—to build up tendon resilience.

And if you really want to prevent problems:

Don’t do the same pull-ups all the time.

Alternate grip width, tempo, movement pattern.

Have you actually checked how you’re doing those pull-ups?

It’s not just about the grip.

Sometimes it’s your technique that’s causing the pain—even if you think your form is flawless.

Here are a few technical mistakes that stress the brachialis:

- Shoulders elevated during the pull (instead of depressed and stable)

- Elbows too wide and flared

- No scapular activation at the start of the movement

- Fast descent with no eccentric control

Fixing these elements can reduce brachialis strain by 30–40%.

A simple tip?

Film your pull-ups from behind and from the side.

Even 10 seconds of footage can reveal if you’re loading asymmetrically or forcing your way through reps.

How to avoid overloading the brachialis in other exercises

The brachialis isn’t just active in pull-ups.

If you feel pain during other pulling movements, you might be overworking it without realizing.

Watch out especially for:

- Neutral grip dumbbell curls (hammer curls), especially when using too much weight or momentum

- Close-grip rows with a barbell or kettlebell

- Pull-ups with super strong resistance bands that fling you upward too fast

Now and then, add a deload week:

- Less volume

- More control

- Focus on mobility and recovery

Your brachialis will thank you.

And what about posture? Does it have anything to do with brachialis pain?

Absolutely.

A closed posture, with internally rotated shoulders, messes with your pull-up mechanics.

If your palms face forward at rest instead of facing your sides, you may have chronic internal shoulder rotation.

This leads to:

- Locked-up scapulae

- Poor external rotation during pull-ups

- Elbows forced into unnatural angles

All of this creates a tension chain that ends right at the brachialis.

Working on:

- Thoracic mobility

- Stretching internal rotators

- Strengthening external rotators

can improve your pull-up form and prevent “chain-reaction” pain.

Chin-ups or pull-ups? It all depends on your elbow

When your brachialis starts complaining, your first question is:

“Okay, then what? Should I just stop pull-ups completely?”

The answer isn’t necessarily total rest.

Often, you just need to switch up your grip.

Classic pull-ups, with palms facing forward, put more strain on the brachialis—especially with a wide grip.

Chin-ups, with palms facing you, completely change the movement dynamics.

They engage the biceps more and, paradoxically, reduce stress on the brachialis.

Not because it stops working (it’s still involved), but because the elbow joint is in a more neutral, forgiving position.

If you’re recovering or trying to avoid issues, chin-ups are one of your best options.

On top of that:

- You can still train intensely

- You’re still hitting your back

- And you might discover your biceps are weaker than you thought

But don’t just swing from one extreme to another.

If you only do chin-ups and overload your biceps every time, you’ll just move the problem elsewhere.

The ideal setup:

- Chin-ups on deload days or when your elbow’s sensitive

- Medium grip pull-ups on stronger days

- Skip wide grip pull-ups unless you’re feeling 100%

RELATED:》》》Which Exercise Is Better, Pull-Up or Chin-Up?

If you’re already injured: how to come back without relapsing

If you’re already in pain, avoid the classic mistake:

“I’ll wait for it to go away, then go back to what I was doing.”

Better to follow a three-phase strategy:

Phase 1 – Stop and unload (5 days)

- No pull-ups

- Ice and gentle massage

- Anti-inflammatory if needed (under medical guidance)

Phase 2 – Reactivation (week 2)

- Ring rows or Australian pull-ups

- Light bands with controlled curls

- Forearm stretching

Phase 3 – Reintegration (weeks 3–4)

- Neutral grip or chin-ups only

- No added weight

- Slow progression

This approach allows you to return to pull-ups without risking a relapse—which is unfortunately very common if you rush the process.

Training for aesthetics? You might not need wide grip at all

If your goal is to build a wider, more defined back, wide grip pull-ups might not be necessary at all.

Muscle growth depends mostly on:

- Motor control

- Sustainable mechanical stimulus

- Smart, progressive volume

Medium or neutral grip pull-ups activate the lats in a safer and more consistent way.

Also, with better technique and less inflammation, you can train more volume per week—and that’s what really drives hypertrophy.

So before getting obsessed with grip width…

Ask yourself: “Is this helping me grow, or just hurting me?”

The brachialis isn’t the only one complaining: other problems from wide grip pull-ups

Okay, the focus so far has been the brachialis.

But if we stopped there, we’d be ignoring other red flags coming from not-so-secondary zones.

When done excessively or without technical control, wide grip pull-ups can cause trouble elsewhere too:

1. Shoulder inflammation (especially the rotator cuff)

The forced abduction and external rotation required by wide grips can lead to:

- Supraspinatus overload

- Subacromial compression

- That snapping or blocking sensation inside the shoulder during the pull

If you feel deep discomfort in your shoulder after pull-ups, or pain when raising your arm overhead…

The culprit may not be the weights—it’s probably your aggressive wide grip pull-up form.

2. Elbow irritation (epicondylitis)

Besides the brachialis, the forearm extensor tendons can also become inflamed due to constant tension—especially if:

- You use a death-grip style hold on the bar

- You never change the bar diameter

- You train while tired with sloppy form

3. Unbalanced pulls from unstable scapulae

A wide grip without scapular control creates chaotic movement patterns.

Instead of retracting and depressing the scapulae at the start of each pull, many people:

- Lead the motion with their shoulders

- Pull using their upper traps

- Compress their neck and upper back

End result?

Neck pain, upper trap tension, and scapulae that wing forward like scared bats.

So: do wide grip pull-ups hurt?

No.

The problem isn’t wide grip pull-ups.

It’s doing them all the time, doing them wrong, and not listening to your body.

They’re a great tool for targeting the lats, improving scapular mobility, and building posture.

But they come at a cost.

If your body’s telling you the cost is too high—pain, inflammation, loss of strength—then it’s time to change strategy.

There’s no glory in wrecking your elbows for a flashy variation.

Real strength is knowing when to dial it back, adapt, and course-correct.

And the beauty is, if you do it in time, your brachialis will come back stronger than before.

And maybe next time you grab that bar with confidence…

He’ll be the first one to thank you.