The gym doesn’t injure people.

Habits do.

There’s a quiet moment that almost nobody talks about.

It’s not the first workout.

It’s not the first time you lift something heavy.

It’s the moment, weeks or months later, when something doesn’t feel right.

Not pain yet.

Not injury.

Just a strange sensation.

A shoulder that feels “off” during presses.

A knee that complains only when you’re tired.

A lower back that tightens after sessions instead of recovering.

Most people ignore that moment.

Not because they’re reckless.

But because nothing dramatic happened.

And that’s exactly how most gym injuries begin.

Not with accidents.

With patterns.

This article is about breaking those patterns before they cost you progress, time, or joints.

Not by training scared.

Not by avoiding intensity.

But by understanding how safety actually works in real gyms, with real people, real fatigue, and real limits.

Gym Safety Is Not About Being Careful

There’s a false idea that safe training means conservative training.

Light weights.

Perfect conditions.

No discomfort.

That’s not how progress works.

Progress requires stress.

Stress requires load.

Load always carries risk.

The goal of gym safety is not eliminating risk.

It’s managing it intelligently.

The people who train for decades aren’t the ones who avoided intensity.

They’re the ones who learned:

- when to push

- when to stop

- when to adjust

- when to rest

Safety is not a brake.

It’s the steering wheel.

Before Training Even Starts

It’s information

If you are:

- new to training

- returning after years

- dealing with chronic pain

- managing cardiovascular issues

a basic medical evaluation isn’t a formality.

It gives you context.

Not permission.

Not restrictions.

Context.

Your heart doesn’t care about motivation.

Your joints don’t care about discipline.

They care about load, recovery, and history.

Knowing those variables lets you train intentionally, not blindly.

Blind training isn’t brave.

It’s inefficient.

Programming is the first safety system

Random workouts create random damage

One of the most underestimated injury risks in gyms is lack of structure.

Not bad form.

Not heavy weights.

Randomness.

When workouts change constantly without logic:

- tissues don’t adapt

- fatigue accumulates unevenly

- recovery becomes unpredictable

A good program does four things:

- It distributes stress across muscles and joints

- It controls progression

- It includes recovery by design

- It reduces decision fatigue

Beginners don’t need variety.

They need repeatability.

Advanced lifters don’t need chaos.

They need precision.

Structure is not boring.

Structure is protective.

Training Frequency

There’s a subtle trap with frequency.

You don’t feel overtrained when you start doing more.

You feel overtrained weeks later.

General guidelines exist for a reason:

- ~150 minutes of moderate activity per week

- or ~75 minutes of vigorous activity

- plus strength work at least twice weekly

But these are anchors, not commandments.

For most beginners:

- 2–3 sessions per week

- full-body or simple splits

This allows tissues to adapt.

For intermediate and advanced trainees:

- 4–6 sessions can work

- only if recovery is respected

Overtraining rarely announces itself loudly.

It shows up as:

- declining numbers

- disrupted sleep

- persistent soreness

- irritability

- loss of motivation

Ignoring these signals doesn’t make you tougher.

It makes injuries quieter — until they aren’t.

Shoes, Floors, and “Unsexy” Safety Choices (Where Most People Get Lazy)

Shoes in the gym are not a detail.

They’re your interface with the ground.

Running shoes:

- soft

- cushioned

- great for cardio

Terrible for heavy lifting.

That cushioning absorbs force — including the force you need to stabilize under load.

For strength training:

- flatter soles

- firmer base

- better force transfer

This isn’t opinion.

It’s mechanics.

And floors matter too.

Slippery surfaces, unstable mats, or uneven platforms increase injury risk even with good form.

Safety often fails at the contact points, not the muscles.

Warming Up

A warm-up is not about “loosening up”.

It’s about:

- increasing tissue temperature

- improving joint lubrication

- preparing the nervous system

Cold tissues resist force.

Resistant tissues tear more easily.

A good warm-up:

- mirrors the session

- activates relevant muscles

- increases range of motion gradually

Five to ten minutes is enough.

If your warm-up exhausts you, it’s wrong.

If you skip it entirely, you’re gambling.

Technique (Why Bad Form Is a Long Game Problem)

Bad technique rarely hurts immediately.

That’s what makes it dangerous.

The body compensates.

Other muscles help.

Momentum steps in.

Until one day it doesn’t.

Good form:

- distributes load

- protects joints

- stays repeatable under fatigue

And here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Most people don’t get injured on their worst reps.

They get injured on slightly bad reps repeated thousands of times.

Technique is not about perfection.

It’s about consistency.

Load vs Fatigue

This is one of the most misunderstood topics in gym safety.

Most people think injuries come from too much weight.

In reality, many injuries come from too much fatigue interacting with weight.

A load that is perfectly safe at the beginning of a workout can become risky 40 minutes later.

Why?

Because fatigue changes how your body moves.

What fatigue actually does to your body

When fatigue accumulates:

- stabilizing muscles lose timing

- coordination drops before strength does

- joint control degrades subtly

- the nervous system looks for shortcuts

You don’t suddenly collapse.

You compensate.

And compensation is where problems start.

The bar path changes slightly.

The knee drifts inward just a bit more.

The shoulder loses centration at the bottom of a press.

Nothing dramatic.

Just enough to increase joint stress.

The dangerous myth of the “last ugly rep”

There’s a common belief that:

“If the last rep isn’t ugly, you didn’t train hard enough.”

That idea has destroyed more shoulders, elbows, and backs than bad programs ever did.

Here’s the reality.

Muscle growth and strength adaptation come from:

- mechanical tension

- sufficient volume

- repeated quality reps

They do not require technical collapse.

When the last reps of every set turn into:

- momentum

- altered range of motion

- joint-dominant movement

you’re no longer training the target tissue effectively.

You’re practicing stress patterns.

A practical rule that actually works

Instead of asking:

“Can I complete this rep?”

Ask:

“Can I complete this rep the same way as the first one?”

When the answer becomes “not really”,

the productive part of the set is usually over.

Stopping there is not quitting.

It’s controlling fatigue.

And controlled fatigue is what allows long-term progression.

Why grinders feel productive but aren’t

This is where the “ugly rep” myth turns into a real training problem.

Grinding reps, those slow, forced reps where bar speed crawls, feel intense.

They feel earned.

They feel like progress.

But grinding reps:

- drastically increase joint stress

- reduce muscle-specific tension

- slow recovery disproportionately

Occasional grinders in controlled contexts are fine.

Living in that zone is not.

Most people don’t get injured because they lift heavy once.

They get injured because they lift tired and heavy all the time.

Pain vs Discomfort (Learning This Difference Can Save Years of Training)

This is a section almost everyone wishes they understood earlier.

Because pain rarely announces itself clearly.

What normal training discomfort feels like

Normal training sensations usually are:

- dull

- spread over a muscle

- symmetrical

- improving as you warm up

Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS):

- appears 12–48 hours later

- feels tender

- decreases with light movement

This is discomfort.

It’s part of adaptation.

What injury-related pain feels like

Problematic pain tends to be:

- sharp or stabbing

- localized to a joint or tendon

- asymmetrical

- worsening as the session progresses

Another red flag is movement alteration.

If you subconsciously change how you move to avoid a sensation, your body is already compensating.

That’s not something to “push through”.

The biggest mistake: waiting for pain to be severe

Many people wait for pain to become unbearable before adjusting training.

That’s backwards.

Pain is a signal, not a verdict.

Early signals are easier to manage:

- reduce volume

- adjust range of motion

- modify load

- improve warm-up and recovery

Ignoring early pain doesn’t make you tough.

It makes the problem louder later.

A simple self-check you can use

After a set, ask:

- Did the sensation stay in the muscle I was training?

- Did it disappear quickly after the set?

- Did my movement pattern stay the same?

If the answer is “no” to more than one,

that’s information worth respecting.

RELATED:》》》 Can a Shoulder Injury Really Bench a Pro Athlete?

Machines and the False Sense of Safety (Why “Guided” Does Not Mean “Harmless”)

Machines feel safe.

They look controlled.

They limit movement.

They remove balance demands.

That’s exactly why people trust them too much.

Why machines can still cause injuries

Every machine has:

- a fixed axis

- a fixed path

- a fixed range

Your body does not.

If the machine’s axis doesn’t match your joint structure,

stress concentrates where you don’t want it.

Common issues include:

- shoulder irritation on chest machines

- knee pain on leg extensions

- hip discomfort on poorly adjusted leg presses

The machine doesn’t adapt to you.

You adapt to the machine.

Sometimes badly.

Setup matters more than people think

Seat height, back angle, foot position, handle grip.

These are not details.

A few centimeters off can change:

- joint angles

- torque distribution

- tissue loading

Many machine-related injuries happen

not because machines are bad,

but because they are set up carelessly.

The “I feel safe, so I’ll push harder” trap

Machines remove the fear of losing balance.

That often encourages:

- higher volume

- pushing through fatigue

- ignoring subtle pain

Ironically, this can increase injury risk.

Free weights often self-limit you.

Machines don’t.

They require even more awareness, not less.

How to use machines intelligently

Machines work best when:

- used as accessories, not ego lifts

- adjusted carefully

- loaded conservatively

- stopped before joint discomfort appears

If a machine consistently irritates a joint,

it’s not “weakness”.

It’s mismatch.

Spotting and Safety With Free Weights

Spotting is often misunderstood.

Help can hurt if done wrong.

A good spotter:

- watches closely

- intervenes only when needed

- does not change the movement path

A bad spotter:

- grabs too early

- pulls unevenly

- distracts the lifter

Both increase injury risk.

When you actually need a spotter

You need a spotter when:

- failure would trap you

- safety pins aren’t available

- fatigue is high and load is heavy

You do not need a spotter for:

- every set

- moderate loads

- movements with safe bailout options

Over-spotting creates dependency.

When lowering the load is the smarter choice

If you don’t trust the setup,

reducing the load is not weakness.

It’s awareness.

Many injuries happen not because people train alone, but because they train beyond their safety margin.

Mental Safety: Why Most Gym Injuries Start in the Head, Not in the Body

This is one of the least discussed topics in gym safety.

Not because it’s unimportant.

But because it’s uncomfortable.

People like to believe injuries are mechanical.

Wrong angle.

Too much weight.

Bad form.

Those things matter.

But very often, the real trigger is mental state.

Training while mentally overloaded

There’s a big difference between training while tired

and training while mentally scattered.

After a long workday, poor sleep, emotional stress, or constant pressure,

your nervous system is already overloaded.

What changes first is not strength.

It’s attention.

You miss small cues:

- bar path drifting

- foot pressure changing

- joint positioning shifting

You don’t feel weak.

You feel “fine”.

That’s the trap.

Your body keeps producing force,

but your ability to control that force drops.

And control is what protects joints.

Why attention fails before strength

From a neurological perspective, this makes sense.

Motor control degrades before maximal output.

Reaction time slows before muscles fatigue.

That’s why people get injured:

- late in the session

- after stressful days

- during “easy” weights

The body can still lift.

The brain is no longer supervising properly.

The phone problem (and why it matters more than people think)

Phones don’t just waste time between sets.

They fragment focus.

Every time attention switches:

- body awareness resets

- readiness drops

- subtle tension patterns change

You step under the bar slightly colder,

slightly less centered,

slightly more distracted.

One time doesn’t matter.

Hundreds of times do.

The gym rewards continuity of attention, not hype.

Rushing is a cognitive risk factor

Training in a hurry changes behavior:

- rest periods shorten unintentionally

- setup gets sloppy

- breathing becomes erratic

Speed without intention is not efficiency.

It’s loss of control disguised as productivity.

Many injuries happen not because the workout was hard,

but because it was rushed.

A practical mental safety rule

Before heavy or complex lifts, ask yourself:

- Am I present right now?

- Am I aware of my body position?

- Am I rushing this set?

If the answer is no, adjust:

- reduce load

- slow tempo

- simplify movement

Training adapts to your mental state, whether you like it or not.

Long-Term Joint Health (Why Feeling Strong Today Can Be the Most Dangerous Signal)

Muscles adapt quickly.

Joints don’t.

That single fact explains most long-term gym injuries.

The mismatch no one talks about

Muscle strength increases in weeks.

Tendons adapt in months.

Cartilage adapts even more slowly.

This creates a dangerous gap.

You feel strong long before your connective tissue is ready.

That’s why many injuries appear:

- after “great progress”

- after rapid strength gains

- when confidence is high

Pain doesn’t show up during adaptation.

It shows up after tolerance is exceeded.

Joint health is a budget, not a feeling

Think of joints like a weekly stress budget.

Every session:

- spends some of that budget

- or restores part of it

Heavy loading without recovery is a withdrawal.

Good technique, smart volume, and variation are deposits.

You don’t feel joint debt immediately.

You feel it years later.

Why “I feel fine” is unreliable feedback

Pain is a late signal.

By the time joints hurt consistently,

the issue has usually been building for months.

Absence of pain is not proof of safety.

Consistency of good habits is.

Variation is protection, not weakness

Repeating the exact same movement,

with the same load, through the same range, week after week, concentrates stress on the same tissues.

Small variations spread stress:

- grip changes

- stance adjustments

- tempo modulation

- range-of-motion control

Variation doesn’t slow progress.

It allows progress to continue longer.

Recovery is joint insurance

Recovery is not a reward for hard training.

It’s a requirement.

Sleep quality.

Nutrition consistency.

Planned deloads.

Skipping recovery doesn’t save time.

It borrows it from the future

with interest.

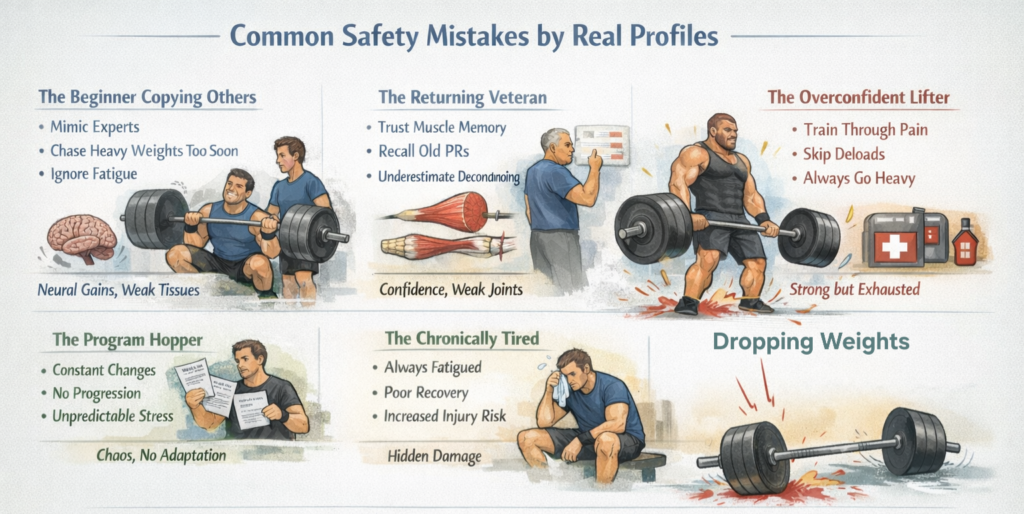

Common Gym Safety Mistakes Made by Real People

Different people get hurt in different ways at the gym.

Injuries are not random.

They follow predictable patterns.

The beginner who copies everyone

Beginners often:

- mimic advanced lifters

- chase load too early

- ignore fatigue

Early strength gains are mostly neural.

Tissues haven’t adapted yet.

This mismatch is one of the highest-risk phases.

The body feels capable.

The joints aren’t ready.

The returner after years off

This is one of the most dangerous profiles.

Formerly trained individuals:

- remember old numbers

- trust muscle memory

- underestimate deconditioning

Muscles come back faster than tendons.

The result is confidence without tolerance.

This is where many “mysterious” injuries happen.

The experienced lifter who never backs off

Experience can become a liability.

Advanced trainees get injured by:

- pushing heavy while fatigued

- ignoring early pain

- skipping deloads

They know how to train hard.

They forget when not to.

Longevity requires humility.

The program-hopper

Constant program changes:

- prevent tissue adaptation

- create unpredictable stress

- remove progression logic

Variety without structure is chaos.

Chaos is difficult to recover from.

The chronically tired trainer

Always training under-recovered:

- dulls pain signals

- alters movement patterns

- increases joint load

Fatigue hides warning signs

until damage is done.

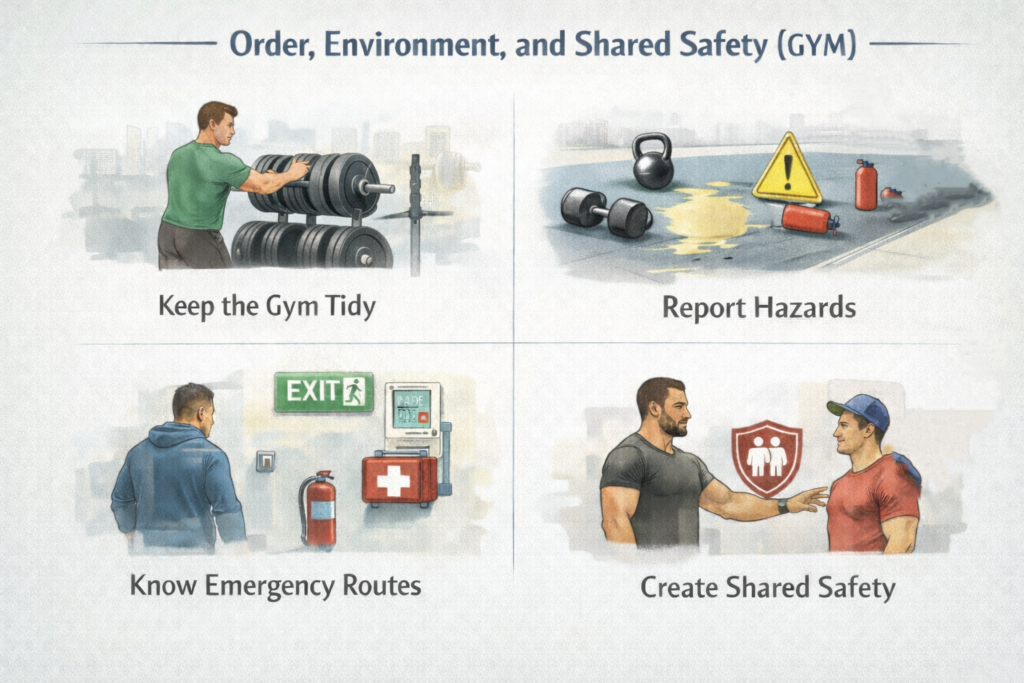

Emergency Awareness (Low Probability, High Consequence)

Emergencies are rare.

That’s why preparation is ignored.

Knowing:

- evacuation routes

- emergency protocols

- defibrillator locations

takes minutes.

Those minutes can matter.

Preparedness is responsibility, not paranoia.

Breathing (Stability, Control, and Safety Under Load)

Breathing affects more than endurance.

It affects joint stability.

Poor breathing:

- reduces trunk stiffness

- increases spinal load

- accelerates fatigue

A simple guideline works for most people:

Inhale during easier phases.

Exhale during effort.

Holding breath without intent increases risk.

Controlled breathing improves performance and safety.

Dropping Weights (Why Control Is Real Strength)

Uncontrolled weight dropping:

- stresses joints

- damages equipment

- creates hazards

Lowering weights under control:

- reinforces technique

- protects tissues

- builds usable strength

Noise is not progress.

Control is.

Cooling Down (The Transition That Protects Recovery)

Cooling down:

- normalizes heart rate

- reduces muscle tone

- initiates recovery

Light movement and gentle stretching are enough.

Skipping cooldowns doesn’t save time.

It delays recovery.

Order, Environment, and Shared Safety

Leaving weights, bars, or plates around is never neutral in a gym setting.

It creates hidden hazards, especially in busy or crowded training areas.

Poor order increases the risk of trips, falls, and unexpected accidents.

Disorganized spaces also raise distractions, pulling focus away from proper technique and awareness.

Mental stress goes up when the environment feels chaotic or unsafe.

Order reduces:

- accidents

- distractions

- unnecessary stress

A clean and organized environment supports safe training, smoother sessions, and shared respect among everyone using the space.

Hygiene and Health Awareness

Clean equipment after use, especially shared bars, benches, and mats.

Wash hands before and after training to reduce the spread of germs.

Avoid training when sick, even if symptoms feel mild.

Use a personal towel and avoid touching your face during workouts.

Cover coughs and sneezes, and dispose of tissues properly.

Basic habits protect everyone and help keep training spaces safe, functional, and respectful.

RELATED:》》》 Why do my knees crack loudly whenever I do slow bodyweight squats?

The Final Safety Checklist (Not Rules — Principles That Work)

You warm up every session.

You train with structure, not randomness.

You stop sets when technique degrades.

You distinguish discomfort from pain.

You adjust load when mentally distracted.

You respect recovery.

You stay aware of surroundings.

You train with intention, not urgency.

This is not caution.

This is intelligence.

For more practical guidance on reducing risk and training smarter, explore the Safe Training resources category:

Final Thoughts (The Only Training That Works Is the One You Can Sustain)

Gym safety is not about fear.

It’s about:

- awareness

- patience

- respect for the process

Most injuries are not accidents.

They are predictable outcomes of ignored signals.

Train with attention.

Train with humility.

Train like someone who wants to keep training for years.

That’s not conservative.

That’s how progress actually works.