Okay, friend.

Let’s have a locker room chat.

It’s back day.

You’re pumped.

Pre-workout circulating like lava in your veins.

Right playlist in your headphones.

You rack up the barbell, perform a row like a Spartan warrior, and then BAM…

Lats on fire.

Biceps pumped.

Traps that look like two mountains.

And the rear delts?

Gone into thin air.

As if they’re on vacation in the Maldives.

No sensation.

No pump.

Nothing.

But why does this happen?

And above all… how the heck do you fix it?

I’m telling you everything.

With some uncomfortable truths, a few tricks to try tomorrow, and a bit of laughter along the way.

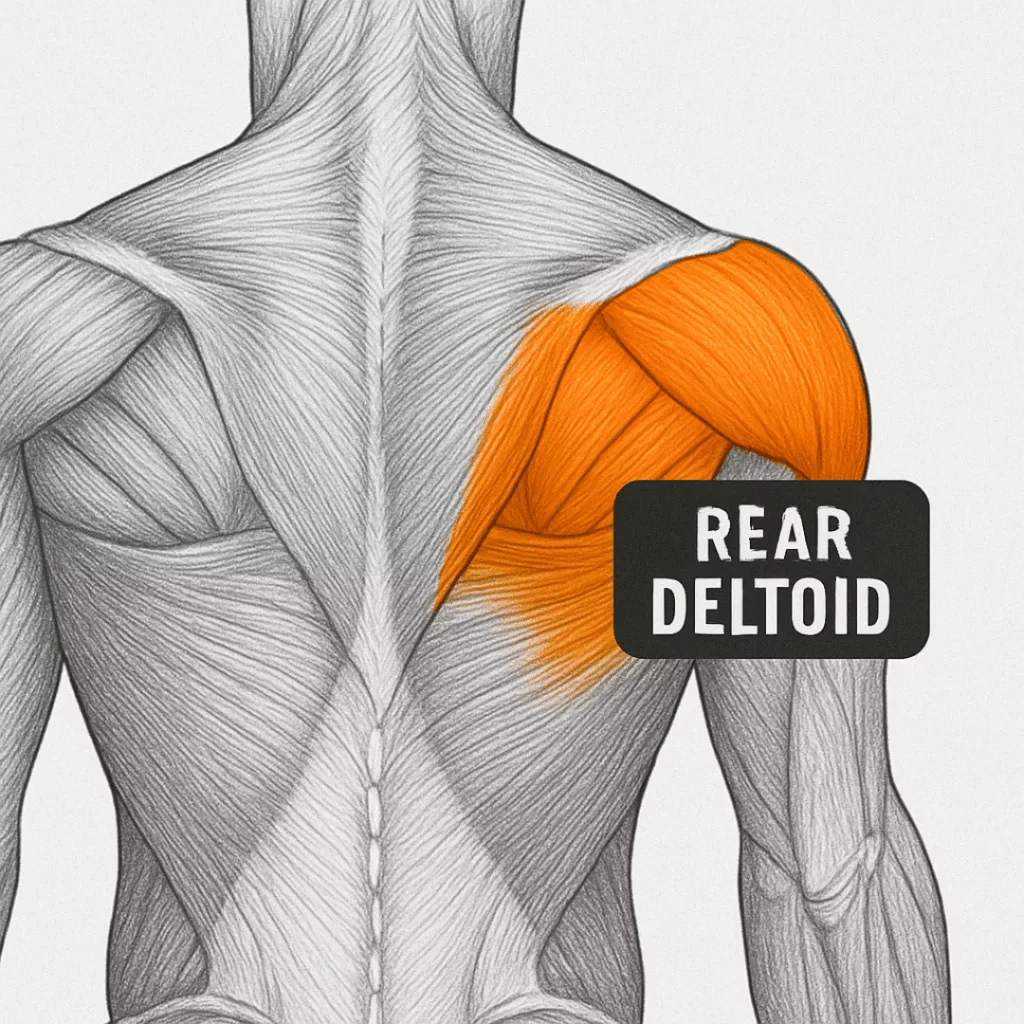

Who Are the Rear Delts, and Why Do They Take It Easy

The rear delts are the “silent cousins” of the shoulders.

They’re at the back, unseen in the mirror (so they’re already at a disadvantage), and they don’t shout for attention like the biceps or chest do.

Anatomically, they’re responsible for horizontal abduction of the shoulder and external rotation.

Translated: they pull the arm outward and backward.

They’re small, but essential.

They stabilize the shoulder, improve posture, and complete that “3D shoulder” look everyone wants.

Without them, you look bulky in the front and… meh in the back.

The Main Problem: Lats Steal the Show

Here’s the deal.

When you do a pulling exercise (rows, pull-ups, pulley, etc.), the lats kick in immediately.

They’re big, strong, and most importantly… they’re the first to say “I’ve got this!”

The result?

They do all the work, along with the traps and biceps.

The rear delts end up as mere wallpaper.

Not because they don’t want to work.

But because no one has asked them properly.

Form (and Angle) Matters. And How It Matters.

If you row with your elbows tight to your torso, you’re telling the lats: “Take it all.”

The rear delts, on the other hand, want a wide angle.

Think of your elbows opening outwards, almost forming a T with your torso.

And above all, you must slow down.

No jerking.

No hip thrusts.

You need to isolate the movement, control it.

The rear delts don’t like chaos.

They want precision, time under tension, slow and sexy movements.

If You Don’t Feel It, It Doesn’t Grow

If you don’t feel the muscle working, you’re not using it to its fullest.

Period.

And this is doubly true for the rear delts.

Studies (and plenty of gym experiences) actively thinking about the muscle during an exercise increases its activation.

So no, you’re not weird if during a set you think, “I want to feel these damn delts!”

Do it.

Focus.

Close your eyes if you have to.

Slow it down.

Feel them work.

The Pre-Fatigue Trick: Wake Them Up First

One of the most effective methods to force the rear delts to participate is pre-fatigue.

What does that mean?

You isolate them with a light exercise before starting your compound moves.

For example:

- 2 light sets of reverse flyes with dumbbells or cables, high reps, maximum control.

You “wake them up.”

Then you move on to rows or pull-ups…

And they activate more because they’re already on alert.

It works.

Proven.

And trust me, you’ll feel it inside.

But I Already Train Them… Maybe Too Much?

Be careful of the opposite too.

If you’re doing too many direct and indirect sets (especially if you’re pushing heavy on military press, snatch, push press, etc.), you might have overcooked them.

And when a muscle is tired, it doesn’t activate well.

It’s like it’s saying, “No thanks, I’m out today.”

So watch your weekly volume.

2–3 targeted sessions per week are enough.

Quality always beats quantity.

Other Factors Sabotaging You (Without You Knowing)

- Desk posture: Are you slouched all day? Shoulders rolled forward? The rear delts stretch too much and become deactivated.

- Zero stretching: Scapular mobility is key. If you’re stiff, the muscle performs poorly.

- Over-reliance on machines: Machines are convenient, but they often “guide” you too much and limit neuromuscular activation.

- Neglected technique: It’s not enough to do the exercise; you have to do it right. Mechanics matter.

Muscles Involved in Pull Exercises: Who Works Behind the Scenes

When it comes to pull workouts, we’re talking about an entire team.

And not one that settles for the bare minimum.

Here are the main players:

- Latissimus Dorsi: The king of back muscles. It originates from the vertebrae and attaches to the humerus. It’s essential for adduction and extension of the arm. It’s what gives you that inverted V look.

- Trapezius (divided into upper, middle, and lower): Controls the elevation and retraction of the scapulae. Fundamental for posture and “pulling correctly.”

- Rhomboids: Work alongside the middle traps to bring the scapulae closer together. Without them, your rows suffer.

- Rear Deltoid: Here we are. It pulls the arm backward and externally rotates it—but only if you activate it properly.

- Biceps Brachii: Often does too much, stealing the spotlight. It assists in elbow flexion.

- Brachialis: Works with the biceps in flexion, but deeper.

- Forearm extensors and rotator cuff muscles: Stabilize the entire shoulder system.

A perfectly orchestrated system—but one that can easily become unbalanced if one part works too much (lats and biceps, I’m looking at you) while another stays lazy (hello, rear delts).

Bent-Over Row with Barbell: Blessing or Curse?

The bent-over barbell row is a classic.

But…

Why don’t you often feel the rear delts?

- Your elbows stay too close to your torso (focus on the lats).

- You use too heavy a load and compensate with a low back or neck.

- You focus on pulling the barbell toward your navel, not toward the upper stomach or sternum.

How to Do It RIGHT

- Feet shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent.

- Bend forward about 45° with a neutral back.

- Pull the barbell toward your nipple line (not your stomach!), opening your elbows.

- Pause at the top.

- Lower it in a controlled manner.

- Maintain tension on the rear delts and upper back.

- Add variations like the snatch grip row to further emphasize the rear shoulder.

Pull-Ups: Why Don’t You Feel the Rear Delts?

Ah, pull-ups.

The ultimate test of gym self-esteem.

But if you don’t feel the rear delts, it’s not their fault.

Here’s why:

- You use a grip that’s too narrow or too supinated (engaging the biceps more).

- You initiate the movement from the arms, not the scapulae (losing scapular retraction).

- You pull upward, but not “backward.”

How to Fix It

- Set a grip slightly wider than your shoulders, pronated.

- Always start with a slight scapular retraction.

- Think about pulling with your elbows downward and slightly backward.

- Be careful not to “close” your shoulders too far forward at the top.

- Incorporate scapular pull-ups as activation before your main sets.

Lat Pulldown and Cable Rows: The Realm of Illusions

These two exercises are loved yet underrated.

And they’re often performed poorly.

The most common issues:

- Pulling with the hands and biceps (zero elbow movement).

- Wrong angle (pulldown too straight).

- No scapular retraction.

- Elbows kept too close: the rear delts sleep.

How to Do Them RIGHT

Lat Pulldown:

- Use a medium-wide, pronated grip.

- Sit properly and lean back slightly.

- Start with the scapulae, then pull your elbows down toward your hips.

- Squeeze hard at the bottom.

- Return slowly.

Cable Row:

- Avoid pulling with just your hands.

- Use different attachments (triangle, bar, rope) to change the stimulus.

- Pull with wide elbows to engage the rear delts.

- Maintain a stable and controlled position.

Building a Strong Back: Exercises and a Weekly Plan

Want a back that looks sculpted in granite?

You need to mix thickness, width, details, and stability.

Key exercises:

- Rows with Variations

- Bent-over barbell row: Already detailed above; use it to develop thickness in the upper back, emphasizing elbow flare.

- Dumbbell row (unilateral or bilateral): Same lean, but with more freedom of movement. Emphasize contraction and improve muscle focus. Great for isolating and correcting imbalances.

- T-Bar row: Grip the handle, lean your torso, and keep your feet wide. Pull the bar toward your chest or stomach, depending on the area you want to target. A narrow grip emphasizes the lats; a wide grip targets the rear delts and upper back.

- Snatch grip row: A wide-grip barbell row variation. Hits the rear delts and entire posterior chain harder. Requires more control and stability.

- Pull-Up / Lat Pulldown

- Pull-ups (pronated grip): Already discussed above; keep your scapulae active and maintain a slightly oblique trajectory.

- Lat pulldown: No need to repeat—it’s been covered. Focus on control and varying your grip.

- Face Pull and Reverse Flyes

- Face pull (with rope on cables): Use a neutral grip. Pull the rope toward your forehead, opening your elbows. At the top, externally rotate your wrists (as if showing your palms). Squeeze maximally, then return slowly.

- Reverse flyes (with dumbbells or on the pec-deck): Keep your arms semi-straight, performing a wide “butterfly” movement backward. Either do this with a bent torso or supported on a bench. Focus on the rear delts, not the traps.

- Cable rear delt fly: A cable variation offering constant tension. Great for isolation work on rear delts.

- Deadlift and Romanian Deadlift

- Deadlift: Feet under the bar, using a mixed or pronated grip. Keep a straight back, drive with your feet, and pull with your hips. Execute an explosive upward movement and a controlled descent.

- Romanian deadlift (RDL): With slightly bent knees, move primarily at the hips. The barbell descends along the thighs to mid-shin. Feel the stretch in your hamstrings and glutes. Excellent for the posterior chain (hamstrings, glutes, lower back).

- Shrugs and Trap Bar Row

- Shrugs: Grip at your sides with relaxed shoulders. Lift your shoulders toward your ears without rotating them. Squeeze at the top, then lower slowly.

- Trap bar row: Grip the trap (or hex) bar, lean your torso, and pull toward your navel with a neutral grip. It’s a great mix between a row and a deadlift, very convenient for those with back or shoulder issues.

Accessory and Mobility Work

-

Band pull-apart: Hold a resistance band at shoulder height with straight arms. Pull it apart until it touches your chest. Perfect for warming up the rear delts and improving scapular control.

-

Shoulder mobility drills: Includes banded external rotations, wall slides, PVC dislocates, and other movements to enhance joint range and reduce injury risk.

Suggested Weekly Training Plan

- Monday (Back Thickness): Bent-over row, T-bar row, Face pull, Deadlift

- Wednesday (Pull and Width): Pull-up, Lat pulldown, Reverse pec deck, Shrugs

- Saturday (Focus on Rear Delts + Mobility): Cable rear delt fly, Snatch grip row, Band pull-apart, Shoulder mobility drills

Extra Tips:

- Use light to moderate weights for isolation movements like face pulls, reverse flyes, and rear delt cable flyes. Prioritize control and mind-muscle connection over load.

- For compound lifts like pull-ups and lat pulldowns, stick to moderate reps (8–12) and emphasize slow, controlled motion—especially on the way down. It’s not about going heavy; it’s about being intentional.

- Don’t chase numbers—chase the burn. If you can’t feel your rear delts working, scale it back and refine your form.

- Keep your chest open and your scapulae moving. Good posture sets the stage for proper activation.

- Include mobility work regularly: banded external rotations, wall slides, and PVC dislocates keep your shoulders happy and your gains sustainable.

How to Know if Your Rear Delts Are Weak

Here are some warning signs:

- “Notre Dame hunch” posture (shoulders forward, protruding scapulae).

- Zero muscle sensation during pull exercises.

- Noticeable asymmetry between the front and back of the shoulders.

- Recurrent shoulder injuries (weakness equals instability).

- Poor control in scapular movements.

A simple test?

Try light face pulls for 15 reps.

If you feel nothing, or only your biceps/traps, there’s work to be done.

Benefits of Regularly Training the Rear Delts

- Improved posture: No more office hunch.

- Injury prevention: A stable shoulder is a happy shoulder.

- Complete aesthetics: A thick back and rounded shoulders from every angle.

- Better performance: In bench, pull-ups, military press.

- Counteracts muscle imbalances: Front delts and chest stop dominating.

Advanced and Less Common Exercises for Rear Delts

If you’re serious, here’s the PRO level:

Reverse Cable Cross

Set the cables low, cross the handles, and pull upward in an “X” shape.

The unique angle hits the rear delts and upper traps with constant tension.

L-Fly on Cable

Anchor your elbow at your side and externally rotate your forearm using a cable.

This hits the rotator cuff and rear delts—perfect for joint health and precision work.

Incline Y-Raise

Lie face down on an incline bench and raise your arms in a “Y” shape.

Slow, controlled, and humbling. Great for scapular control and rear delt isolation.

Landmine Rear Delt Row

With your torso inclined and hands gripping the bar sleeve, row toward your upper chest using wide elbows.

Hits the rear delts with a unique resistance path—great for variety and overcoming plateaus.

These exercises hit the rear delts from different angles and in various ways.

Few do them.

You’ll be among the few who are smart.

Grip and Hand Spacing: When They Matter and Why

The grip changes everything.

- Tight and supinated: More emphasis on the biceps.

- Wide and pronated: More activation of the upper back and rear delts.

- Neutral: A good mix, useful for both cables and dumbbells.

- Snatch grip (extra wide): Superior activation of the rear delts.

When to Change Your Grip

- If you don’t feel the target muscle.

- If you hit a plateau in your progress.

- If you experience joint pain.

- If you want variety without changing the exercise.

RELATED:》》》 Deltoid Development: Should You Isolate the Front, Side, and Rear?

Conclusion

Not feeling them doesn’t mean they’re not there.

It means you’re not speaking their language.

They’re muscles that need to be conquered.

Educate yourself.

Stimulate them with patience.

They might not show up immediately, but when they explode…

They completely change your posture, aesthetics, and strength.

So from today, stop treating them like background extras.

Make them the stars.

Give them the attention they deserve.

Because there’s nothing more satisfying than looking in the mirror and seeing those rounded shoulders, with the back finally present and sculpted.

Still here?

Good on you.

Now you have no more excuses.

You already have everything you need.

Your rear delts are watching…

And they expect you to finally bring them into the spotlight.