Have you ever looked in the mirror after a shoulder workout, drenched in sweat, thinking:

“Okay, but why do my shoulders still look like the wings of a raw chicken?”

Been there. Done that.

And that’s when I realized one fundamental thing: shoulders, or rather the deltoids, aren’t built by chance.

And above all, they don’t grow just by saying, “Oh, I’ll do a few lateral raises and that’s it.”

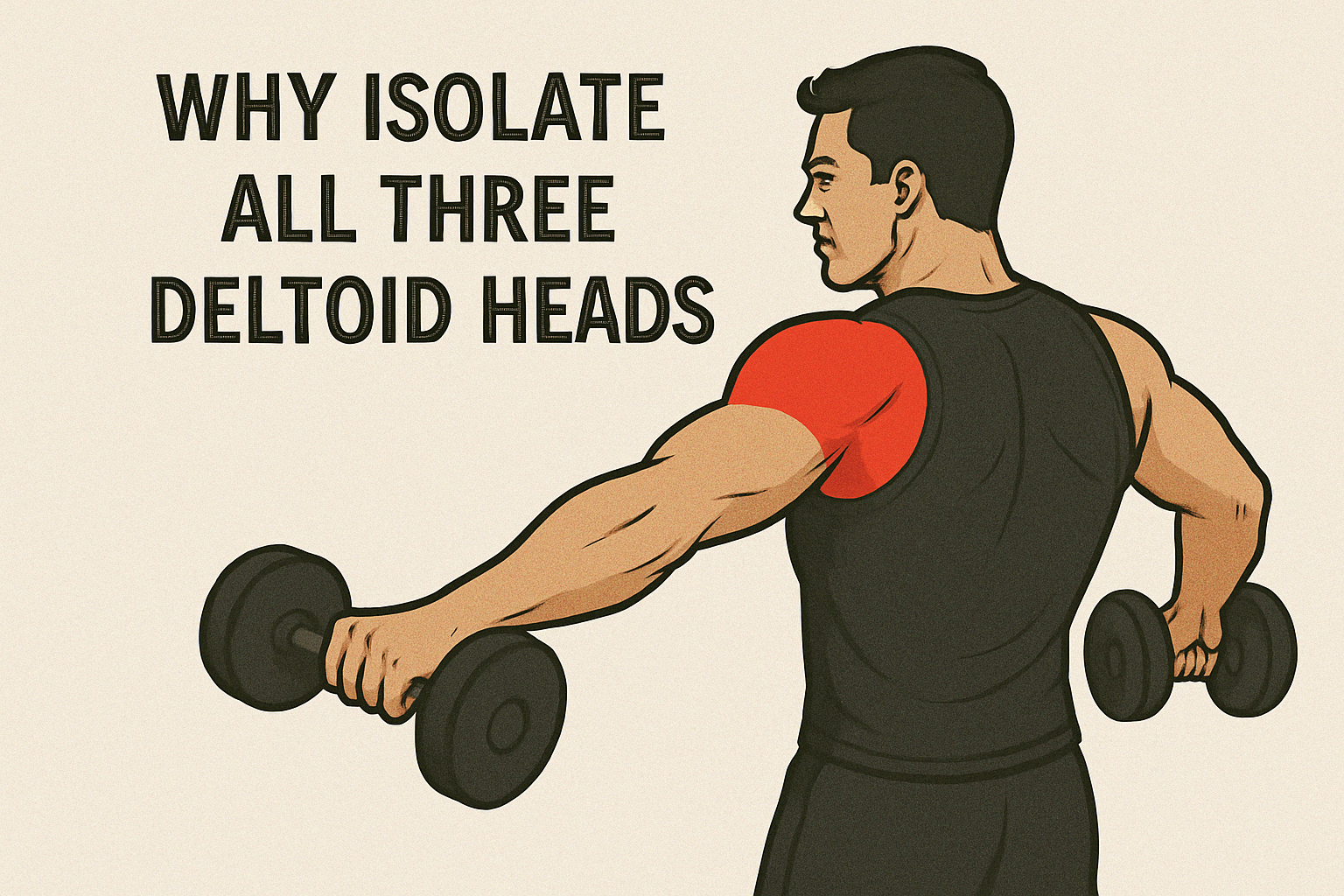

Know Your Enemy (or Objective): The Three Heads of the Deltoid

The deltoid is like a ’90s boy band: it has three components, each with its own role, but they all need to come together to make an impact.

Anterior Deltoid

It’s at the front. It comes into play during forward pushing and overhead movements.

Lateral Deltoid

It’s what gives you width. It pushes the arm outward.

Posterior Deltoid

It’s at the back. It assists with backward movements and helps with posture.

If you train only one or two, disaster happens: the shoulder loses harmony, becomes unbalanced, and visually… meh.

Why Doing Only the Military Press Is a Rookie Mistake

I used to be convinced that simply lifting a barbell overhead was enough to become a titan.

Military press, dumbbell press, Arnold press… I thought, “I’m working hard, so I’ll grow everywhere.”

Spoiler alert: only the anterior deltoids grew.

The lateral ones?

Ignored.

The posterior ones?

I assumed they were the back’s job.

But no.

Presses are great, but they deliver a one-way hit.

The rest of the shoulder is just there, watching with folded arms and a long face.

If you really want mass, you can’t get away with one single compound movement.

You need to sharpen your weapons and target each head with specific exercises.

My Turning Point: When I Stopped Wingin’ It

I remember the day I realized something was off.

I had been training for months, yet my side profile looked like that of a tired penguin.

Then I took a good look at my shoulder routine.

Everything was presses.

No isolation work.

Zero rear delt raises.

Not a decent lateral raise in sight.

That’s when I changed everything.

I introduced:

- Lateral raises (even with an isometric pause at the top – pure pain)

- Face pulls – eternal love for this exercise

- Reverse flyes – done properly, controlled, slow

And guess what?

My shoulders started to take shape.

Boom.

Width.

Depth.

Volume.

And even the occasional compliment like, “Oh, you’ve really been pushing yourself, huh?”

Deltoids and Functional Strength: Not Just Aesthetics

Yes, okay, we’re always talking about mass, shape, lines, proportions.

But the deltoids aren’t just there to make us look like a Marvel action figure.

They are functional muscles.

They are needed to lift, rotate, throw, push, pull, carry things overhead, and even stabilize your torso.

A weak deltoid—especially the posterior—can cause serious problems:

- Compensation in other muscle groups (e.g., overactive traps)

- Compromised posture

- Rotator cuff pain

- Reduced power in sports movements

Training the three heads separately also helps build a stable, reliable, and high-performing shoulder—not just one that looks good on the cover.

Differences Between Men and Women in Deltoid Training

It’s another aspect that’s often overlooked.

A muscle is a muscle, sure.

But the response to training can vary between men and women, especially due to hormonal distribution and joint structure.

Women, having on average more slow-twitch fibers, respond better to high volume and moderate-high repetitions (12–20 reps).

Men, with more fast-twitch fibers and higher testosterone, also do well with heavier loads and lower repetitions.

But the golden rule applies to both: all three heads need to be stimulated, just with slightly different strategies.

And no, ladies: don’t be afraid of “getting too big” in the shoulders.

It won’t happen by accident.

It only happens if you make it happen, with years of work and a meticulously dialed-in diet.

Deltoid Training and Sports: Focus on Specific Performance

If you’re an athlete—or even just a sports enthusiast—this matters to you.

Every sport stresses the deltoids in different ways:

- Boxing and MMA – dominant anterior deltoid for direct punches and protection

- Swimming – significant involvement of the lateral and posterior for traction and rotation

- Volleyball, basketball, tennis – require total balance to avoid injuries

Training each head in isolation helps you:

- Prevent imbalances and overuse

- Improve sport-specific technique

- Reduce the risk of inflammation (like tendinitis and impingement)

In short, even if you’re not aiming for the bodybuilding stage, training the deltoid heads separately is a winning strategy for performance sports as well.

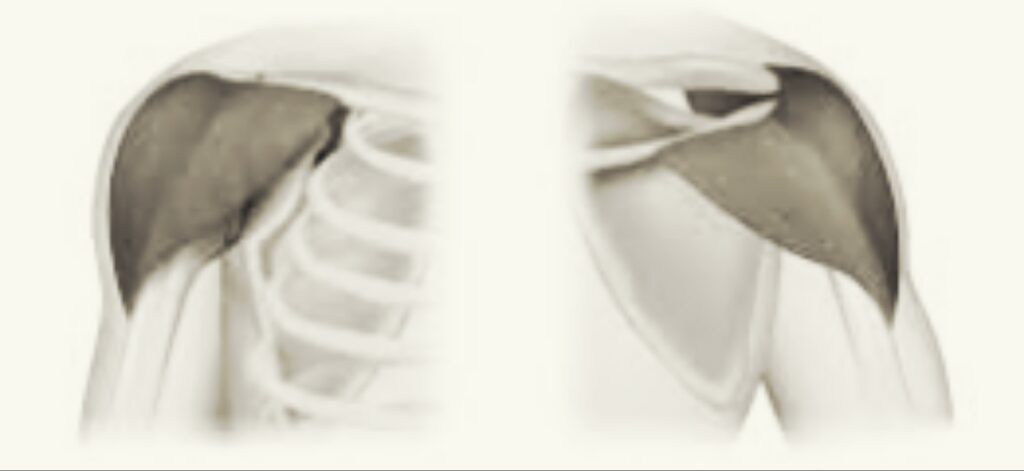

Is It Extremely Difficult to Develop Big Posterior Deltoids? And… Are They Really Important?

Yes, my friend, let’s say it without filters: the posterior delts are tricky.

They grow slowly.

They don’t respond as noticeably.

Often, you can barely see them in the mirror.

So what do most people do?

They ignore them.

A monumental mistake.

The posterior deltoid (or rear delt, as friends call it) is crucial for:

- Balancing shoulder posture (especially if you do a lot of bench pressing and overhead pressing)

- Adding depth and a three-dimensional look to your shoulder profile

- Preventing rotator cuff injuries

- Stabilizing pulling and overhead movements

Why are they so stubborn?

Because you hardly use them in everyday life.

And in workouts… if you don’t isolate them, they won’t activate properly.

Moreover, they’re small and often overpowered by the traps and back muscles, so you have to learn to feel them.

That’s where surgeon-like precision is required.

Face pulls, reverse flyes, band pull-aparts, rear delt cable flyes.

These exercises aren’t flashy, but they’re pure gold if you want that extra detail behind the shoulder that makes the difference between “okay” and “wow.”

How Often Should I Train Each Deltoid Head?

The golden rule here is simple: balanced frequency + targeted stimuli.

But it should also be personalized based on:

- How developed your deltoids are now

- Which other muscle groups you train (e.g., chest and back influence the shoulders)

- Recovery and diet

A general guideline for an intermediate trainee:

- 2–3 times per week with a differentiated focus

For each deltoid head, consider:

- Anterior:

- Frequency: 1–2 times

- Sets per session: 3–4

- Reps range: 8–12

- Rest: 60–90 sec

- Lateral:

- Frequency: 2–3 times

- Sets per session: 4–5

- Reps range: 10–15

- Rest: 30–60 sec

- Posterior:

- Frequency: 2–3 times

- Sets per session: 4–5

- Reps range: 12–20

- Rest: 30–45 sec

The posterior head can handle high volume.

The lateral head demands constant, isolated tension.

The anterior head… is often already heavily worked by pressing, so be careful not to overdo it.

A Simple and Clear Intermediate Program: Balanced Stimulus for All Three Heads

Here’s a “basic yet effective” weekly plan, designed for those with some experience who want solid results without going crazy with 10 variations per head.

Day 1 – Push (with an anterior and lateral focus)

- Dumbbell military press – 4×8 (targets anterior and stabilizers)

- Dumbbell lateral raises – 4×12-15 (targets lateral)

- EZ-bar front raises – 3×10 (targets anterior)

- Cable face pulls – 3×15-20 (lightly targets posterior)

Day 2 – Pull (posterior focus)

- Reverse flyes on an incline bench – 4×15-20 (targets posterior)

- Band pull-aparts – 3×20-30 (targets posterior)

- Cable rear delt fly – 3×12-15 (targets posterior)

Day 3 – Shoulder Accessory (lateral focus and isolations)

- Single-arm low cable lateral raise – 4×12-15

- Cable reverse fly – 3×15

- Disc front raise – 3×10

- Shrugs for the traps – 3×12 (bonus)

Execution tips:

- Controlled movement

- Stop when you lose control of your range of motion

- A 1-second isometric pause at the contracted position during isolation exercises

This program is sustainable, comprehensive, and adaptable for push/pull splits or full-body routines.

Powerlifting vs. Bodybuilding: Different Approaches for the Deltoids

In powerlifting, the deltoids are “tools,” not the end goal.

The focus is on specific strength to improve the bench press.

Thus, the anterior deltoid is heavily trained, while the other two are seldom emphasized.

Key exercises include: overhead press, push press, and board press.

In bodybuilding, on the other hand, the deltoids are part of the aesthetic package:

Each head is trained in isolation to maximize shape and symmetry.

Exercises like lateral raises, rear flyes, and controlled presses are key.

The focus is on tension, angles, and volume.

In summary:

The powerlifter looks for strong shoulders to push more weight.

The bodybuilder seeks big shoulders to resemble a Greek statue.

Both can learn something from each other.

Training Deltoids to Failure: Yes or No?

This is the million-pound question.

And as always… it depends.

What does “failure” mean?

It’s the point at which you can’t perform another repetition with good form.

When should you use it?

For isolation exercises (lateral raises, front raises, flyes):

Yes, you can go to failure more often.

These exercises stress the nervous system very little, and the risk of injury is low.

For compound exercises (military press, overhead press):

It’s better to avoid total failure, especially on heavy sets.

The risk of compensating (especially with the lower back) and injury increases.

Recommended strategy:

- Controlled failure on lighter exercises or machines

- Leave 1–2 reps “in the tank” on heavy exercises

- Use failure as an occasional technique (last set, finisher, drop set)

Training to failure every time can slow recovery, increase the risk of overtraining, and compromise performance in subsequent sessions.

Growth happens with a constant and progressive stimulus, not by wrecking yourself every time.

Conclusion

Shoulders are like a signature at the bottom of a painting.

They aren’t everything, but when they’re there, they stand out.

They make your chest appear wider.

They improve your posture.

They give you that look of “yes, I seriously work out.”

And they don’t require miracles.

Just an intelligent plan, a bit of controlled suffering, and a lot of consistency.

Stop neglecting them.

Give them a name.

An identity.

A role.

Classic Questions I Get on the Topic (and the Honest Answers)

“Even if I do a lot of compound exercises, isn’t that enough for all the deltoid heads?”

No. Compound movements often underutilize the posterior head.

“Am I at risk of overtraining my shoulders?”

Only if you don’t recover properly or plan your training well.

The shoulders are resilient, but balance is key.

“Better barbell or dumbbells?”

Both.

But dumbbells offer more freedom and less joint stress.

Mixing them up is ideal.

Okay, so: do I really need to train the three heads of the deltoids separately?

Absolutely.

If you’re content with flat or imbalanced shoulders, then ignore it.

But if you want full, round, harmonious shoulders, then it’s not optional.

It’s a necessity.

Three heads.

Three functions.

Three different approaches.