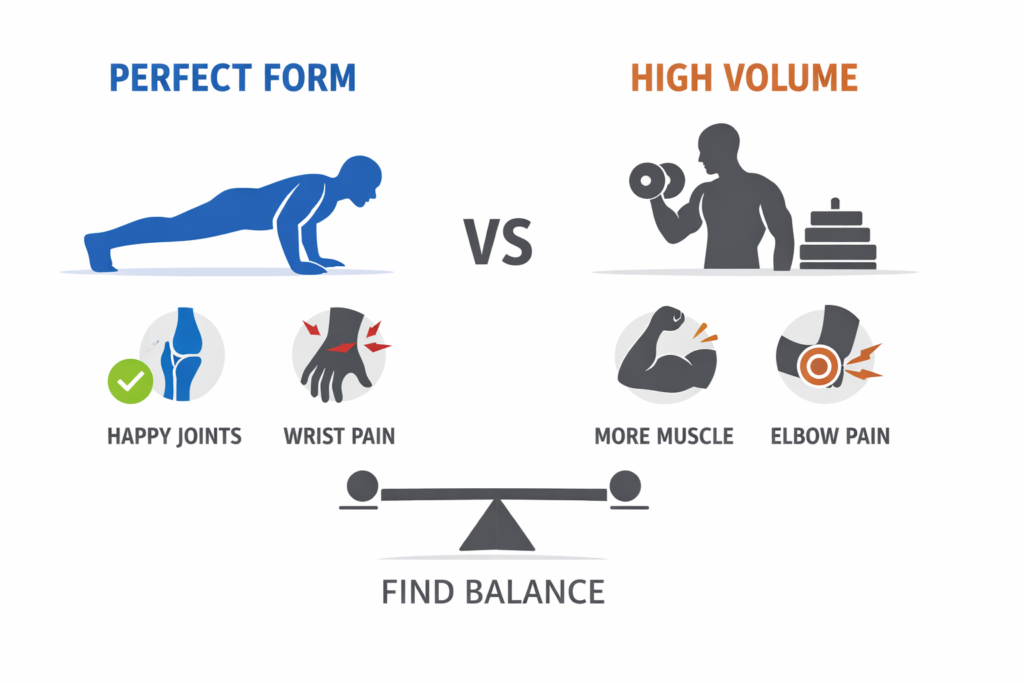

Two loud opinions kept popping up across the fitness world.

On one side, perfect form was treated like a software update that magically fixes everything.

Across the room, another camp insisted volume was the real engine, and technique only needed to be “good enough.”

Instead of arguing with imaginary people in my head, I decided to test both ideas in training.

A few of the results were predictable.

A few were not.

What I Actually Compared

Rather than constantly changing exercises, I kept the main movements consistent.

The difference came from how those movements were performed.

Perfect form meant textbook-clean reps.

Controlled tempo from start to finish.

Full range of motion without rushing or cutting corners.

No momentum, no ego, and sets ended the moment technique started to fade.

High volume shifted the focus toward total work across the week.

More sets.

More reps.

More total time under load.

Less obsession with every rep looking museum-ready.

High volume doesn’t automatically mean bad form.

It means inviting the body into a negotiation.

That conversation doesn’t always use words.

Sometimes it shows up as a very specific, very localized sensation near a tendon.

A few of those messages were genuinely unexpected.

The Small Decisions That Changed How Training Felt

I trained 4 days a week.

Two upper-body focused days and two lower-body focused days.

I also walked most days because my brain behaves better when I do.

I didn’t chase failure on every set.

Most sets ended with about 1–3 reps left in the tank, meaning I could’ve done a couple more reps if I absolutely had to.

That matters because “everything hurts” is a common outcome when every set is a life-or-death event.

I also kept my warm-up consistent.

Five to eight minutes of easy movement, then a few lighter sets of the first exercise before the real work.

No magical mobility ritual, no candles, no summoning ancient shoulder spirits.

And I wrote down discomfort in plain language.

Not “my kinetic chain is compromised.”

More like “front of shoulder feels pinchy when I press overhead.”

What I Actually Did (Explained Like You’ve Never Heard the Names Before)

I used a pretty normal list, because the point wasn’t novelty.

The point was to see what happens when the same patterns are trained with different priorities.

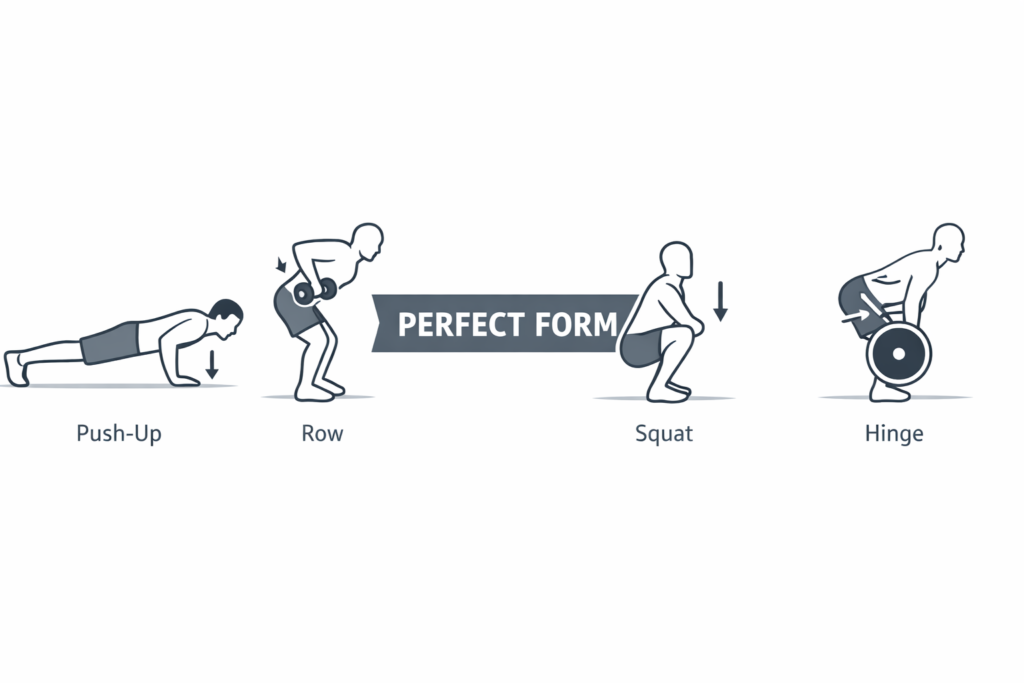

Push pattern (chest/shoulders/triceps) included pressing movements.

Think of a push-up: hands on the floor, body rigid like a plank, lowering your chest, then pushing back up.

That basic pattern can be made harder with incline, decline, rings, dumbbells, or a barbell.

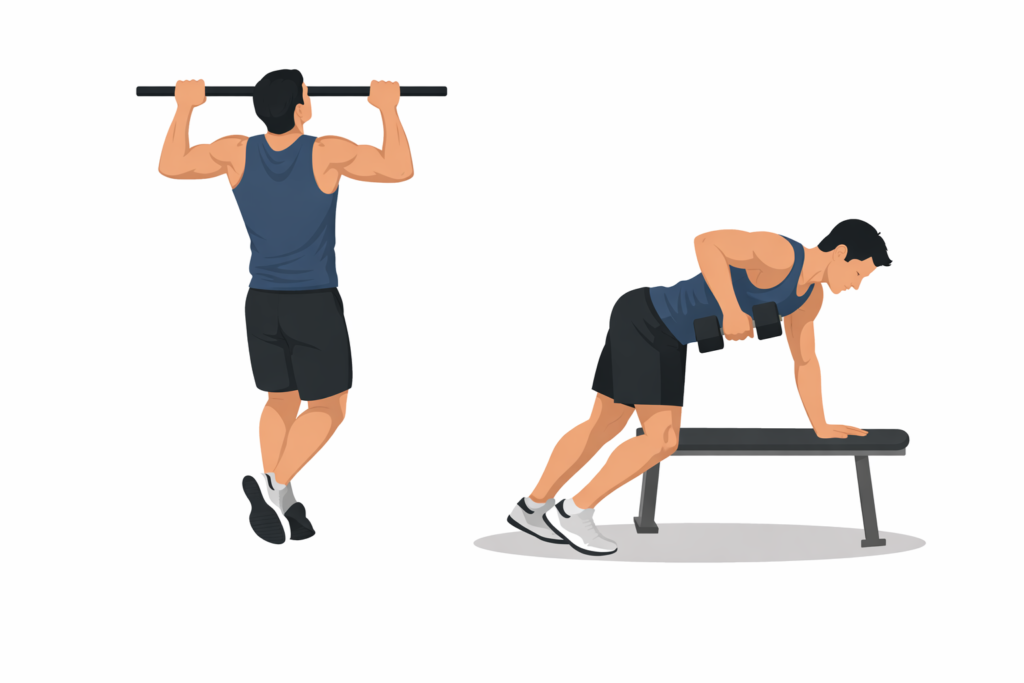

Pull pattern (back/biceps) included rows and pull-ups.

A row is pulling something toward your torso while keeping your trunk stable.

A pull-up is hanging from a bar and pulling your chest upward by driving your elbows down.

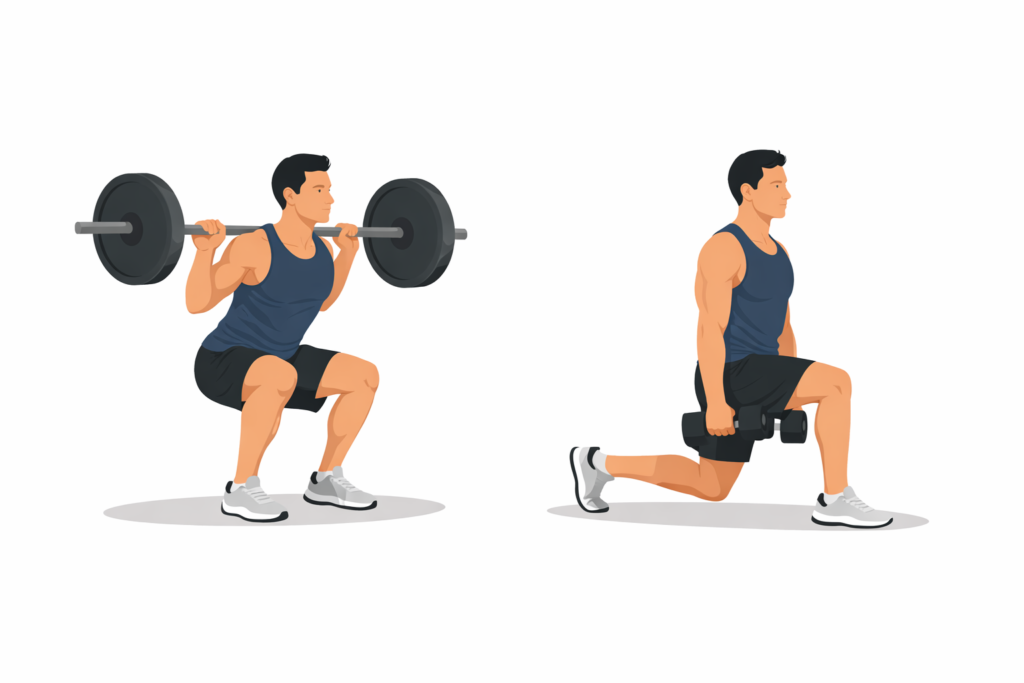

Squat pattern (legs) included squats and split squats.

A squat is bending knees and hips to lower your body, then standing back up.

A split squat is similar but with one foot forward and one foot back, so each leg works more individually.

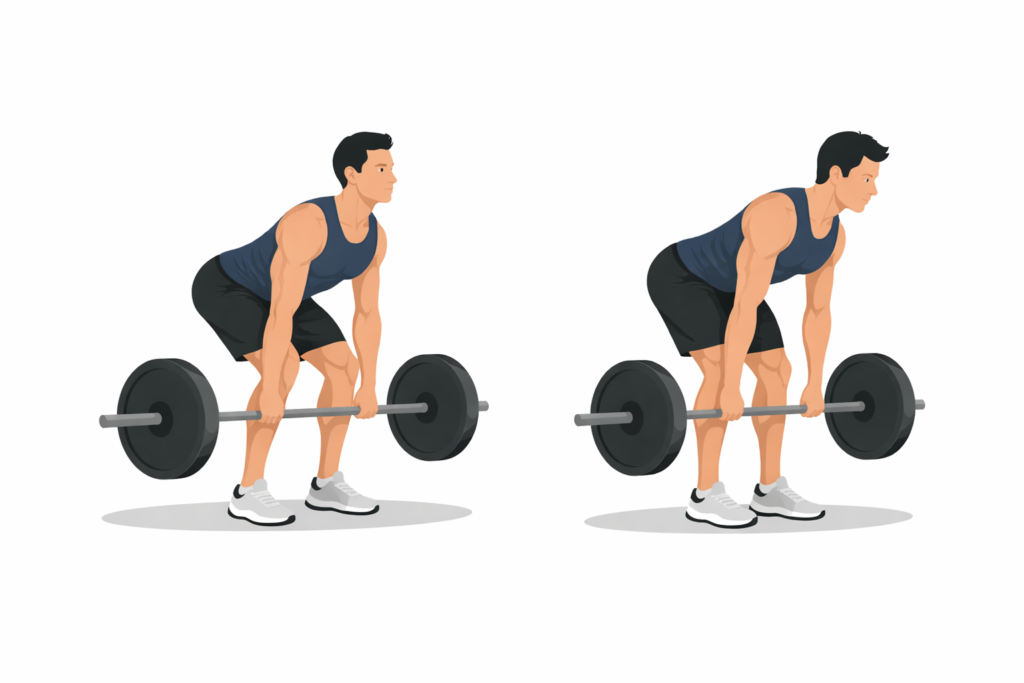

Hip hinge pattern (glutes/hamstrings/back) included deadlift-style movements.

A hinge is folding at the hips with a relatively neutral spine, like closing a car door with your butt while your hands hold groceries.

For core, I used simple anti-extension and anti-rotation work.

That means resisting being pulled into a banana shape or twisted like a towel.

Planks and suitcase carries are classic examples.

Nothing exotic.

Just the stuff that usually builds muscle and strength when done consistently and intelligently.

1. When I Trained Like a Form Purist

This period felt amazing at first.

Not “Instagram amazing,” but calm, clean, and weirdly satisfying.

I slowed down reps on purpose.

Lowering for about two to three seconds, pausing briefly where it made sense, then lifting without jerking.

That slower tempo made lighter loads feel heavier, which is great when you’re trying to respect your joints.

Here’s what “perfect form” looked like for my main movements.

On push-ups, I kept a straight line from head to heels.

Hands were under or slightly wider than shoulders, elbows moved at a natural angle, and my chest touched the floor without my hips sagging.

If my neck craned forward like a curious turtle, I reset.

On rows, I stopped using momentum.

That meant no “start the rep by launching my torso,” and no shrugging the shoulder up to my ear at the top.

I pulled with the elbow, squeezed my upper back, and kept the ribcage from flaring like I was trying to flex invisible abs.

On squats, I controlled the descent and didn’t chase depth at the cost of spinal position.

Knees tracked roughly over the toes, feet stayed planted, and I didn’t collapse inward like a folding chair.

I treated the bottom position like a checkpoint, not a crash landing.

On hinge movements, I focused on hip movement first, not low back movement.

Shins stayed relatively vertical, hips moved back, and the spine stayed neutral instead of rounding like a question mark.

I stopped reps if I felt the “stretch” move from hamstrings to lower back.

Volume here was moderate.

Enough to make progress, not enough to make me feel like I was living inside a set counter.

What Hurt During the Form-First Phase (And What Didn’t)

Let’s start with the good news.

Most joints felt quiet, which is basically the highest compliment your body can give you.

My knees felt better than usual.

Slow squats and controlled split squats let my legs do the work instead of relying on tendon bounce.

I also noticed less irritation around the front of the knee, which is often a sign you’re dumping stress where it doesn’t belong.

My lower back was shockingly calm.

The hinge cue of “hips back, spine neutral” reduced that vague fatigue I sometimes get from sloppy bracing.

It felt like my hamstrings and glutes were finally doing their job instead of outsourcing everything to my lumbar spine.

My shoulders mostly behaved.

Pressing with control, and not letting elbows flare aggressively, reduced that front-of-shoulder pinch I used to feel.

It wasn’t magic, it was just better alignment and less chaos.

Now the “what hurt” part, because bodies always want a subplot.

My wrists started complaining during push-ups.

Not sharp pain, more like a persistent “hey, we’re bent back a lot here.”

When you slow down reps, you increase time in that extended wrist position, and my wrists noticed.

My upper traps got tight from being too “careful.”

I was so focused on controlling every rep that I sometimes over-braced and held tension where it didn’t help.

It was like driving a car with your shoulders instead of your hands.

My elbows were fine in this phase.

Which matters, because the elbow is the kind of joint that will let you know when your volume bill is overdue.

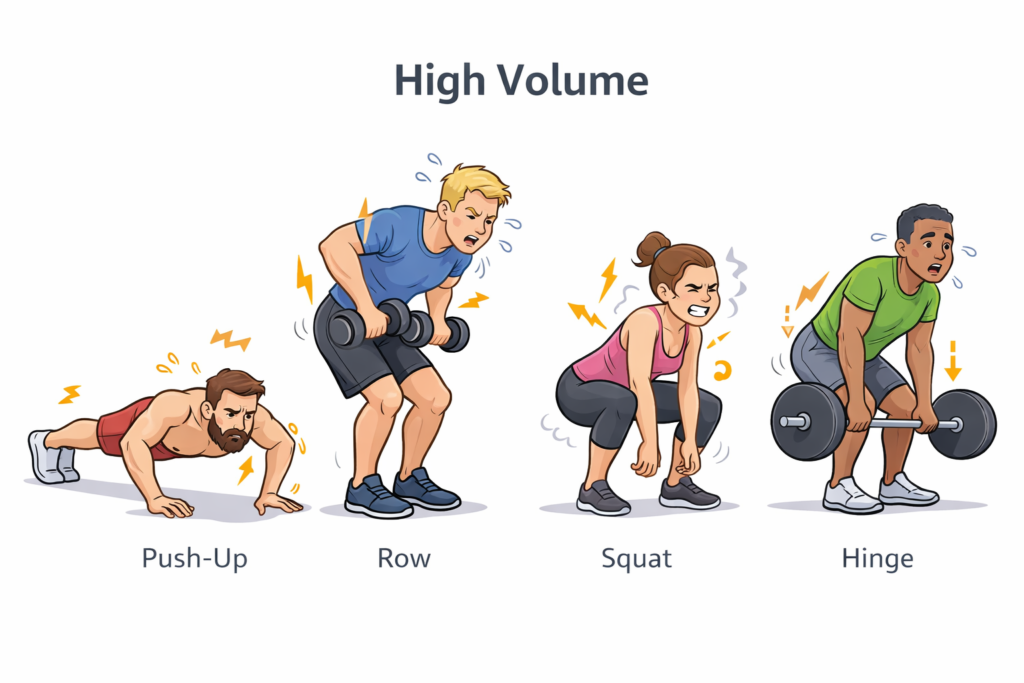

2. When I Pushed High Volume and Let “Good Form” Be the Goal

That chapter felt productive in a different way.

Not cleaner, not prettier, but like I was stacking more total work and forcing adaptation.

I kept technique standards, but I stopped treating every rep like an exam.

Form stayed solid, but I allowed a normal training rhythm.

Reps were still controlled, just not slow enough to make every set feel like underwater typing.

Volume went up mostly through extra sets and extra weekly frequency of certain patterns.

More total pulling, more total pressing, and more accessory work for arms and shoulders.

Leg work also increased, but I was careful because high-volume legs can turn walking into a negotiation.

This is the part where a lot of people accidentally do something sneaky.

They increase volume and intensity at the same time, then blame “volume” when they get wrecked.

I tried to keep intensity reasonable so the only big change was total work.

My workouts started feeling longer.

Not dramatically, but enough that recovery became a real factor instead of a theoretical one.

And my joints started giving feedback faster.

What Hurt During the High-Volume Phase (And What Didn’t)

My muscles felt fuller and more “trained,” which is the obvious upside.

But the first thing that changed wasn’t muscle.

My elbows started feeling cranky on pulling days.

Not during the first set, but later in the session, especially on movements where the grip was tight and the elbow flexed hard.

It wasn’t an injury moment, it was a slow accumulation thing, like browser tabs piling up until your laptop fan starts screaming.

The discomfort showed up around the inside of the elbow sometimes.

That area often gets irritated when forearm flexors and gripping muscles get overloaded.

High volume means more gripping, more pulling, more repeated stress on tendons that don’t always recover as fast as muscle.

My front shoulder also had a couple “pinchy” days.

It happened when pressing volume rose and I got lazy with shoulder blade control.

If the shoulder blade doesn’t move well, the ball-and-socket joint ends up trying to do everything alone, and it’s not built for that kind of overtime.

My knees were mostly okay, but only because I managed fatigue carefully.

When volume increased, sloppy squats showed up sooner, especially if I rushed rest times.

Knees don’t love being the emergency brake for a tired hip.

My wrists actually felt a bit better than the form-purist phase.

Shorter time under tension per rep meant less time hanging out in wrist extension.

So yes, my wrists preferred the phase that looked less “perfect,” which is both annoying and very realistic.

My lower back stayed fine as long as I respected hinging fatigue.

Once I added too many hinge-related sets in the same week, I felt that dull tightness creeping in.

That was a warning, not a disaster, but I listened because lower backs don’t bluff for fun.

The Biggest Pattern I Noticed: Tendons Hate Sudden Promotions

Muscles adapt relatively fast.

Tendons adapt slower, and they get irritated when you ask for a job upgrade overnight. (I broke this down more in “Why Slow Eccentrics Feel Weird on Tendons.”)

High volume made my muscles feel like they were leveling up.

But elbows and shoulders started acting like middle managers under stress.

Not broken, just grumpy, and grumpiness is often a preview.

Perfect-form training reduced joint complaints, but it came with its own trade-offs.

More time under tension made wrists talk more, and excessive “control mode” made me hold tension where it didn’t belong.

It was like running a game on ultra settings and realizing your system is stable but your fan is working overtime.

Why Perfect Form Didn’t Automatically Mean “No Pain”

Perfect form is not a force field.

It’s more like driving carefully in the rain.

Careful driving reduces risk.

Careful driving doesn’t guarantee nobody slides, especially if the road has oil patches you didn’t see.

Also, “perfect” is a slippery word.

A squat that is perfect for one hip structure might irritate another.

A press that feels smooth for one shoulder might pinch another depending on mobility, anatomy, and training history.

What perfect form did give me was earlier signals.

When reps are controlled, you feel small deviations faster.

And that makes it easier to adjust before the body escalates the complaint.

Why High Volume Didn’t Automatically Mean “More Injuries” Either

High volume isn’t evil.

It’s just loud.

Volume exposes weak links because it gives them more chances to complain.

If technique is decent, recovery is decent, and progression is gradual, volume can be tolerated surprisingly well.

The problem is when volume goes up while sleep, stress, and nutrition stay the same.

The other issue is exercise selection.

High volume with joint–friendly movements can be fine.

High volume with movements that already irritate you is like poking a bruise repeatedly to see if it stopped being a bruise.

In my case, high volume didn’t wreck me.

It just made certain areas predictable hotspots: elbows, sometimes front shoulder, sometimes general fatigue management.

That’s not failure, that’s information.

The Practical “So What”: How I’d Train Now After Living Through Both Styles

If I could rewind and choose only one style forever, I wouldn’t.

Because each style solved a different problem.

Perfect-form emphasis made my training safer and more sustainable.

It cleaned up movement, reduced joint noise, and made me feel “in control” again.

That’s especially valuable after a break, after an injury scare, or when life stress is high.

High volume made my body adapt in a more obvious way.

Muscles responded, work capacity improved, and I felt more athletic in daily life.

But it demanded smarter recovery, smarter exercise selection, and more humility with tiny aches.

So the approach I’d keep is a blend.

Form-first as the foundation, volume as the tool, and progression as the rule.

Where Most People Get This Right (and Still Mess It Up)

Most good reps share the same quiet feeling.

They’re stable, controlled, and repeatable.

When a rep starts feeling like something you have to catch instead of move, that’s the first warning sign.

Slowing things down usually fixes more than changing exercises ever will.

Push-ups fall apart long before they look ugly.

Elbows drift out, wrists collapse, and the body starts bending in places it shouldn’t.

Bringing the hands under the shoulders and controlling the descent cleans most of it up.

Angry wrists usually mean the setup needs help, not more grit, so elevating the hands or using handles keeps things neutral.

Rows give away control through momentum.

The torso starts the movement, shoulders climb toward the ears, and the elbow stops leading the pull.

Resetting the brace, pulling with the elbow, and trimming sets does more for elbow health than chasing extra reps ever will.

Squats expose balance issues at the bottom.

Chasing depth without control leads to knees drifting and the spine doing the work instead of the hips.

A slightly shorter range with solid tracking builds strength faster than collapsing into the hole.

Hinges are the easiest place to cheat without noticing.

When the stretch shifts from hamstrings to lower back, the hips have stopped doing their job.

Reducing hinge volume early prevents the kind of tightness that turns into forced rest later.

Progress rarely fails because of effort.

It usually fails because too many variables change at once.

Adding one thing at a time keeps tendons adapting instead of complaining.

RELATED:》》》 How to Lift Safely While Still Making Progress

Wrapping Up: The Pain Made Sense, and That’s a Good Thing

The stuff that hurt wasn’t random.

Wrists didn’t love long, slow pressing.

Elbows didn’t love lots of gripping and pulling volume.

Front shoulders didn’t love pressing volume when scapular control got sloppy.

The stuff that didn’t hurt was also not random.

Knees and back stayed happier when reps were controlled and fatigue was managed.

That’s the boring truth, and boring truth is usually what keeps people training for years.

If the goal is progress without feeling fragile, the answer isn’t choosing a side.

The answer is using form to build a stable base, then using volume like a dial you turn gradually.

Not like a switch you slam because motivation hit at 11 PM.