There’s a moment in the life of anyone who trains when the couch stops being just a couch.

It becomes an obstacle.

It becomes an improvised rack.

It becomes the place where you set a dumbbell down “just for a second” and then find it there three weeks later, like an archaeological artifact.

If you’re thinking about a home gym, you’ve probably already lived at least one of these scenes.

Maybe you trained in a gym for years and now want autonomy.

Or maybe you started training at home, got excited, and then discovered that space isn’t infinite and neither is your patience for assembling and disassembling equipment every time.

That’s the exact moment when the modern marketing miracle of fitness enters the scene: the all-in-one home gym.

One machine.

A thousand exercises.

Zero compromises, at least on paper.

The problem is that paper doesn’t have to squat, doesn’t have to handle progression, and doesn’t have to coexist with a real apartment.

This guide exists for one reason only.

To help you buy smart.

To help you avoid the most common mistake of all.

Choosing equipment based on the idea of your “super consistent” self instead of your real-life Tuesday-evening version.

What you’ll get by reading to the end

By the end of this article, you’ll know:

How to decide whether an all-in-one actually makes sense for you or if it will just make you want to sell it on Marketplace.

Which modular alternatives offer more results per square foot.

How to choose equipment that grows with you instead of locking you into the “fitness introduction” level.

How to design a training corner that doesn’t turn into an elegant storage dump.

How to avoid invisible costs, meaning time, frustration, and “I don’t feel like it because I have to set everything up.”

On top of that, you’ll have a clear structure for building a home gym by goal, by profile, and by lifestyle.

The first rule of the home gym

Space comes before equipment

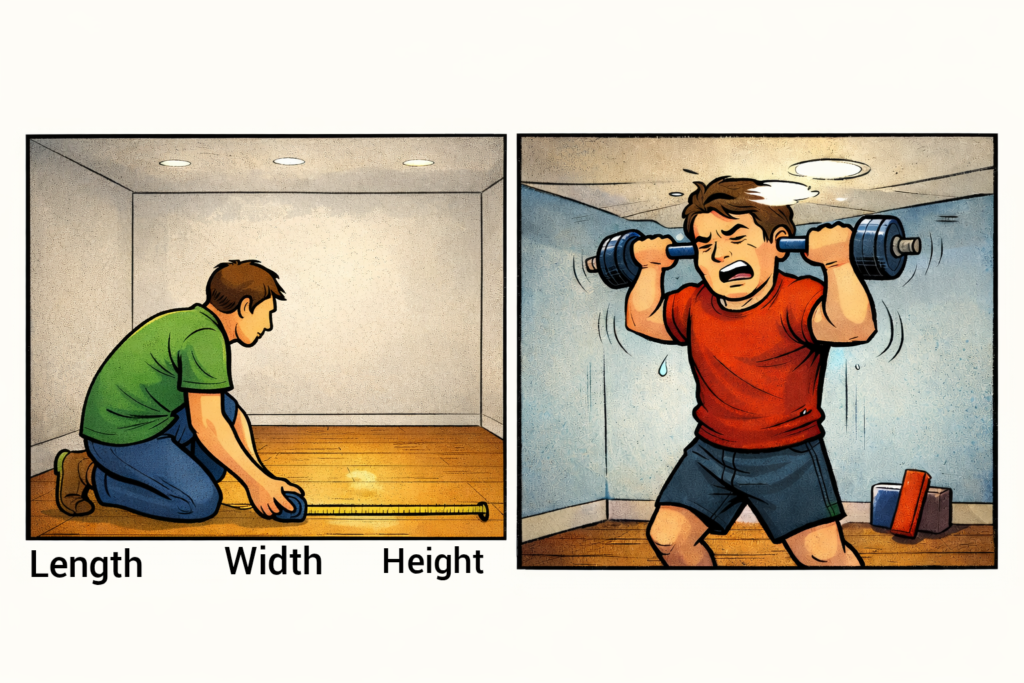

Before looking at prices, reviews, or “today only” deals, measure.

Measure for real.

Length.

Width.

Height.

Height is the part almost everyone ignores and then discovers during the first overhead press.

A low ceiling can make simple movements unusable, like jump rope, burpees, overhead presses, pull-ups on a high bar, even some dumbbell extensions.

A piece of equipment might technically fit “at rest” and still be unmanageable “in use.”

A multi-station often needs lateral space for cables.

A treadmill needs space behind it for safety.

An adjustable bench needs room in front and behind so you can position yourself and get up without doing acrobatics.

The goal here isn’t to make everything fit.

The goal is to move naturally.

The second rule of the home gym

The real enemy isn’t lack of motivation

The real enemy is friction.

Friction means:

I have to move furniture.

I have to assemble pieces.

I have to adjust ten things.

I have to be careful not to scratch the floor.

I have to put everything away, and that alone already tires me out.

An effective setup reduces friction in an almost boring way.

Boring, in this case, is a compliment.

When starting is easy, training becomes normal.

When starting is complicated, training becomes “a project.”

And a project, after a long day, often loses to a hot drink and a TV series.

Is an all-in-one home gym worth it?

Honest answer: it depends, but much less than you think.

In the real world, an all-in-one makes sense in very specific situations.

Outside of those situations, it often turns into an expensive object you’ll “get back to eventually.”

Let’s look at both cases, without poetry.

When an all-in-one can be a smart choice

An all-in-one can work well if:

Your space is stable and dedicated, even if small, and you don’t have to dismantle everything every time.

You want guided, linear training, with little desire to build routines and variations.

You prefer fixed movement paths because they make you feel safer.

You’re mainly interested in general fitness, toning, maintenance, or recomposition without chasing heavy progression.

Multiple people will use the machine and you want one “standard” solution for everyone.

You already have enough experience to adapt exercises and not get fooled by “1,000 exercises” when in reality you’ll use 12.

In these cases, an all-in-one can become a sort of “modular kitchen.”

It’s not the kitchen of your dreams, but it’s functional, tidy, and it does its job.

When an all-in-one tends to be a costly mistake

An all-in-one is often a bad idea if:

Your goal is to build strength and muscle with serious long-term progression.

You enjoy training with freedom of movement and real variation.

You want to combine strength, conditioning, mobility, and accessories without feeling boxed in.

You know you train better when you can change stimulus without reconfiguring half a machine.

You have limited time and every setup minute eats away at your motivation.

You want equipment that you can expand and keep using even if you change house, room, or training style.

With many all-in-ones, the problem isn’t that they don’t work.

The problem is that they work well only inside a fence.

That fence is made of:

Ranges of motion that aren’t always natural.

Resistance that reaches its ceiling quickly.

Exercises that are “possible” but uncomfortable.

Angles that don’t respect your body structure.

Cables that change the resistance curve differently than you expect.

If you train with structure, sooner or later you notice that some things become constant compromises.

A constant compromise is a mental tax.

Mental tax makes workouts disappear.

The mental trap of the all-in-one

“One tool, so I’ll always use it”

It sounds logical.

It’s like buying a Swiss Army knife and thinking you’ll cook better for the rest of your life.

The Swiss Army knife is amazing while camping.

In the kitchen, after a while, you want a real knife.

With all-in-ones, the same thing often happens.

At first, you do everything.

After a month, you only do the movements that are most comfortable.

After three months, you start avoiding what requires long adjustments.

After six months, you’re left with a big machine that gives you the same five exercises over and over.

Not because you’re lazy.

Because you’re human.

Marketing sells you “features”

You should be buying “solutions”

A feature is:

“1,000 exercises available.”

A solution is:

“I can train back and legs in 40 minutes without wasting time setting things up.”

A feature is:

A solution is:

“I can push, pull, and isolate with easy progression and comfortable paths.”

When you evaluate an all-in-one, always ask yourself:

Does this actually solve my main problem?

Or is it just charming me with a feature list, like a gaming PC that I end up using to write emails?

The alternative that wins in about 70% of cases

A modular setup, small but smart.

For most people, a modular setup beats an all-in-one on three fronts:

Real versatility.

Longer progression.

Less daily frustration.

On top of that, a modular setup is scalable.

You add pieces when you need them.

You don’t have to replace everything as you evolve.

If you like nerd metaphors, think of a custom PC.

An all-in-one is a closed laptop, elegant, with limited upgrades.

A modular setup is a desktop.

You can change one part without throwing away the whole system.

The four pillars of the smart home gym

Whenever you choose equipment, always evaluate these four points.

Versatility means how many movement patterns you can train without forcing awkward positions.

Progression means how long you can increase load, difficulty, or volume without getting stuck.

Safety means stability, realistic loads, and the ability to exit a rep without getting into trouble.

Low friction means fast setup, easy adjustments, and order.

If a tool is great in three areas and terrible in one, that one area is usually what ruins the experience.

The tools that give the most value per square foot

We’re not doing a “Top 25” list here.

We’re choosing what, in practice, covers the most needs with the least space.

Adjustable dumbbells

Adjustable dumbbells are the best compromise between:

Strength.

Hypertrophy.

Conditioning.

Accessory work.

When they’re well designed, they replace an entire rack of fixed dumbbells.

The huge advantage is simple progression.

Simple progression lets you improve without constantly redesigning everything.

Pay attention to two things, though.

The mechanism must be solid and fast.

The handle must be comfortable and stable.

If changing weight takes too long, the heart of the workout turns into an assembly tutorial.

Resistance bands

Bands are underrated because they look “rehab-only.”

The reality is that they add a tension curve that dumbbells and barbells don’t.

On pushing and pulling movements, they can:

Make the lockout more demanding.

Improve control.

Allow higher volume without destroying your joints.

They’re also perfect for warm-ups and mobility, which is the part everyone says they do and then skips.

The beauty of bands is that they don’t demand space.

They only demand creativity and a solid anchor point.

Pull-up bar, preferably multi-grip

A pull-up bar is as close as you get to a legal training hack.

It takes up almost no space.

It trains back, arms, grip, and core.

It offers long-term progression.

A multi-grip version helps you choose angles that are friendlier to shoulders and elbows.

If you’ve had joint discomfort, grip choice is like changing your mouse after years of wrist pain.

It seems minor.

Then suddenly you understand why it mattered.

Suspension trainer

A TRX-style system turns a door or anchor point into dozens of exercises.

Difficulty adjusts through body angle.

This is perfect for home use because:

You don’t need to buy tons of weights.

You don’t need to switch tools every two minutes.

You can train strength, control, core, and functional patterns without chaos.

The only serious requirement is a reliable anchor.

If the anchor is improvised, the experience suddenly becomes very “real” and not very fitness-friendly.

Adjustable bench, ideally foldable

The bench is a multiplier.

With dumbbells and no bench, you’re often stuck standing or on the floor.

With a bench, you unlock:

Pressing variations.

Supported rows.

Seated curls.

Incline work.

More comfortable core and accessory training.

A foldable version reduces friction and keeps the room livable.

This is the part many people ignore.

A home gym has to coexist with your home.

If the house feels invaded, mental resistance kicks in, even if the equipment is great.

Adjustable kettlebell

An adjustable kettlebell is perfect for:

Conditioning.

Hip hinge patterns.

Explosive work.

Full-body training.

On top of that, the swing is one of the best time-to-benefit movements when done well.

The main limitation is technical.

A badly done swing is a great way to regret your choices the next day.

If you want to use it properly, learning the basics is worth it.

Mat and recovery tools

A decent mat is not an “accessory.”

It’s the foundation for bodyweight work, mobility, and recovery.

Foam rollers and massage balls aren’t magic.

They’re tools.

Tools that help manage stiffness and keep your routine sustainable.

Sustainability beats heroic intensity.

Always.

The comparison everyone avoids – All-in-one vs modular, in real life

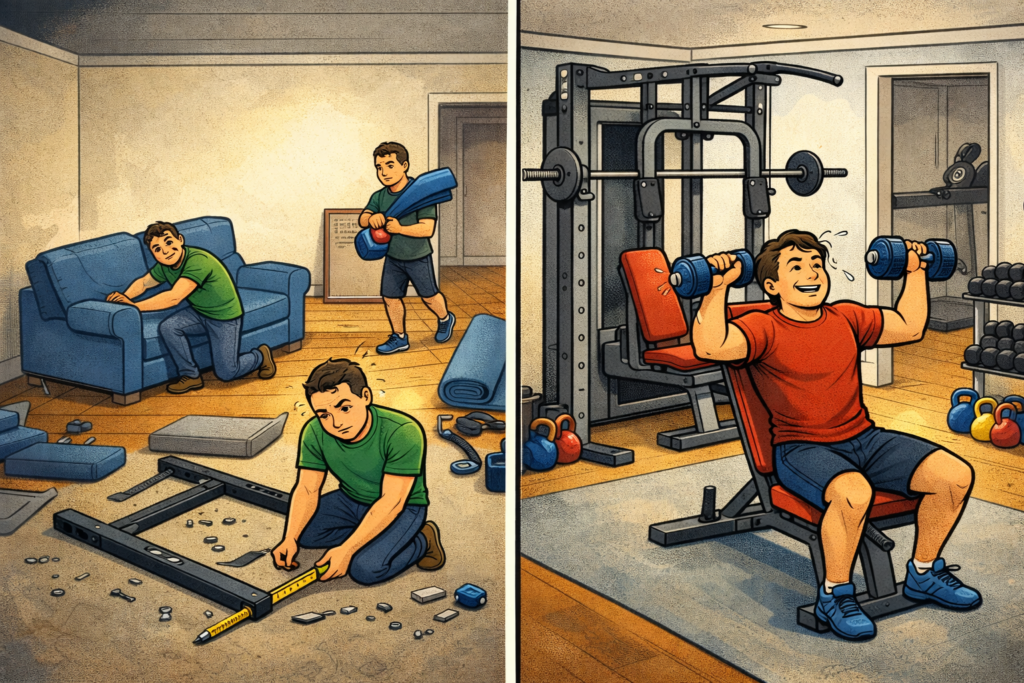

Imagine two scenarios.

Scenario A.

You buy an all-in-one.

You have one tidy station and the feeling that “now I have everything.”

Scenario B.

You buy adjustable dumbbells, a bench, a pull-up bar, bands, and a suspension trainer.

You have more pieces.

You have more freedom.

Now look at what happens after three months.

With the all-in-one, you start doing the same movements that require fewer adjustments.

With the modular setup, you start discovering combinations.

With the all-in-one, progression becomes “add some and see.”

With the modular setup, you can micro-load, change ranges, and adjust stimulus easily.

With the all-in-one, leg training often stays limited unless the station is truly large.

With the modular setup, legs get trained through split squats, RDLs, goblet squats, lunges, hip thrusts, step-ups, and endless variations.

With the all-in-one, conditioning usually requires external creativity.

With the modular setup, circuits happen naturally.

Neither choice is “always wrong.”

One is simply more suited to people who want results over time with fewer constraints.

The technical point that actually matters

Progression is not optional.

If you train to feel better, progression doesn’t mean becoming a powerlifter.

Progression means your body keeps receiving an adequate stimulus.

If the stimulus never grows, improvement stops.

If it grows too fast, discomfort and setbacks appear.

A good setup allows gradual, easy progression.

The ideal tool makes you say:

“Today I add a little and keep going.”

It doesn’t force you to say:

“I can’t add a little, so I add too much or nothing at all.”

This is one of the limits of many home machines.

Load jumps aren’t always smooth.

Resistance curves aren’t always intuitive.

Working ranges aren’t always comfortable.

With dumbbells and bands, you usually have more control.

The most common mistakes that ruin a home gym

1# Buying equipment before building a routine

Many people buy as if the equipment itself were the solution.

The solution, instead, is the habit.

Equipment helps the habit when it makes starting easy.

If you don’t yet know how you’ll really train, buying a big machine is like buying a grand piano while you’re still deciding if you like music.

It’s better to start with tools that allow many paths.

2# Underestimating setup time

Five minutes sounds like nothing.

Five minutes, three times a week, becomes an invisible barrier.

The invisible barrier is what makes you say “not today” without even noticing.

Winning tools are the ones that are “already ready.”

3# Ignoring flooring and noise management

A home gym doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

It lives on a floor.

It lives near neighbors, family members, and fragile objects.

Mats and protective flooring are investments, not decorations.

Reducing noise and vibration increases the chance that you’ll train without stress.

Training without stress increases consistency.

4# Trying to replicate the gym perfectly

Home is not the gym.

Trying to miniaturize the gym often creates frustration.

The best home gym isn’t the one that copies the gym.

It’s the one that uses the advantages of being at home.

Zero commute time.

Flexible schedules.

Short but frequent sessions.

Micro-workouts.

Integrated accessory and mobility work.

Designing for human profiles, not just “levels”

Profile 1: little time, 30–40 minute windows

You need equipment that allows fast transitions.

Adjustable dumbbells with quick changes help a lot.

Bands and suspension trainers allow smart supersets without switching stations.

A ready bench reduces dead time.

Here, all-in-ones often lose because they require frequent adjustments to change exercises.

Profile 2: shared space, need for order

Here, storage matters.

Foldable bench.

Compact adjustable dumbbells.

Bands in a simple container.

Wall- or door-mounted pull-up bar with clean installation.

A large all-in-one can feel invasive, even if it technically fits.

Psychological invasion weighs as much as physical invasion.

Profile 3: serious strength and muscle goals

The most solid path usually includes:

Stable bench.

Heavy dumbbells or a barbell and rack, if space allows.

Pull-up bar.

Structured progression.

If you truly want to push heavy loads, a rack is often more useful than a multi-station.

Rack safety and barbell freedom are hard to replicate with home machines.

Profile 4: general fitness and sustainability

Here you want variety without complexity.

Dumbbells plus bands plus a suspension trainer cover almost everything.

A kettlebell adds conditioning and power.

A decent mat turns the room into a mini studio.

In this profile, an all-in-one can work, but it’s often unnecessary.

Quality and longevity

How to spot solid equipment without getting hypnotized

Quality is not an adjective.

It’s a checklist.

Durable materials, especially where load and movement meet.

Stability, with wide bases and non-slip surfaces.

Adjustment mechanisms that don’t feel like a puzzle.

Realistic load capacities, not creatively written ones.

Clear warranties and available spare parts.

Cheap equipment often doesn’t “break immediately.”

It starts doing small, annoying things.

It creaks.

It shifts.

It wobbles.

It makes natural positions uncomfortable.

Those small things become reasons to postpone.

Postponing is the first step toward not training.

Ease of use

A home gym should be as easy as brushing your teeth.

Not because it’s boring.

Because it’s effective.

If every workout requires ten minutes of preparation, your brain starts treating training as a rare event.

If it only takes two minutes to start, training becomes part of the day.

A good test is this.

Imagine you’re tired today.

Imagine you slept badly.

Imagine you still have 25 minutes available.

Does your setup make you say “okay, I’ll do something”?

Or does it make you say “not worth it”?

That difference determines results more than the model of the equipment.

A practical guide to building your home gym

(From zero, without waste, with a clear path)

Step 1: define your main goal

Choose the focus.

Strength and muscle.

Conditioning and fat loss.

Mobility and wellness.

General fitness.

The focus doesn’t prevent you from doing other things.

The focus prevents you from buying randomly.

Step 2: choose a core of 3–5 items

A very effective typical core can be:

Adjustable dumbbells.

Foldable bench.

Resistance bands.

Pull-up bar or suspension trainer.

Mat and basic recovery tools.

With this, you can train:

Push.

Pull.

Legs.

Core.

Conditioning.

Mobility.

At that point, your home gym is already “complete.”

Step 3: add only when a limit is real

A real limit is:

“I can’t progress in this movement because I lack a tool.”

A non-real limit is:

“I saw a video and it looks cool.”

The video doesn’t live with you.

The video doesn’t pay for the space.

The video doesn’t move the treadmill when you want to clean.

Step 4: build a layout that invites use

Put the most-used tools where you can see them.

Hiding everything looks tidy but often increases friction.

Leave a clear space to move.

Treat that open square as sacred.

If you want to be really practical, think in terms of “stations.”

Strength station with dumbbells and bench.

Mobility station with mat and bands.

Pull station with bar or suspension trainer.

Each station should take only seconds to start using.

If you want cardio, you don’t need a monster in the living room

Cardio at home can be simple.

Jump rope.

Step platform.

Rowing machine, if you have space and want a serious tool.

Bike or treadmill only if you’ll truly use them.

The classic mistake is buying a treadmill as if it were a subscription to consistency.

In practice, it often becomes a luxury clothes rack.

Not always, but often enough to deserve a bittersweet smile.

How to choose equipment that evolves with you

The right upgrade isn’t buying more, it’s buying better.

Look for tools that allow:

Small increments.

Easy variations.

Use in multiple contexts.

Adjustable dumbbells with a wide range support years of progression.

Bands of different resistances add stimulus without taking space.

Suspension trainers remain useful even as you get stronger, because you can increase leverage and instability.

Pull-up bars grow with added load, tempo, and variations.

An all-in-one often grows less well because upgrades are limited.

Once you outgrow its sweet spot, you end up replacing everything.

One encouraging truth

You don’t need the perfect home gym.

You need the used home gym.

A $300 home gym used three times a week beats a $3,000 home gym used three times a month.

Consistency always beats aesthetics.

Training at home isn’t “less serious.”

Training at home is a strategy.

The strategy works when it removes obstacles and makes training natural, almost inevitable.

If you choose well, home becomes the place where you take care of yourself with less stress.

If you choose poorly, home becomes the place where you feel judged by a machine staring at you from the corner.

That machine, by the way, has no right to judge anyone.

Quick final decision

Three questions that clarify everything:

1) Do you train better with freedom or with a guided path?

Freedom points to modular.

Guided paths can favor a multi-station.

2) Is your space dedicated or shared?

Shared space favors foldable, compact tools.

Dedicated space opens larger options.

3) Do you want long-term progression or simple, practical fitness?

Long-term progression favors dumbbells, bench, pull-up bar, and possibly a rack.

Practical fitness can work with more constrained solutions if they’re comfortable.

Conclusion

An all-in-one home gym can be useful, but only in specific scenarios.

In most cases, a well-planned modular setup offers more results, more freedom, and less friction.

The best choice comes from three things.

Real, measured space.

A clearly defined goal without heroic fantasies.

Tools selected for versatility, progression, safety, and ease of use.

Starting with a few good pieces is often the smartest move.

Adding gradually is often the most sustainable path.

Training at home becomes easy when the environment invites you in, not when it challenges you.