That question used to annoy me.

Not because it’s “wrong,” but because it sounds like it should have a simple answer.

Strength equals muscle.

Muscle equals size.

End of story.

Except… the mirror doesn’t always agree.

So this is the long version.

No guru vibes.

No “just trust the process.”

Only what I noticed, what I tested, what changed when I flipped variables one at a time, and what I wish someone had explained earlier.

The Setup: Getting Stronger While Looking… Mostly The Same

At some point my calisthenics numbers started to look “serious” on paper.

Strict pull-ups were high-rep and clean.

Weighted pull-ups climbed steadily.

Dips stopped feeling like a chest exercise and started feeling like a warm-up.

Muscle-ups became consistent, not lucky.

Then the annoying part happened.

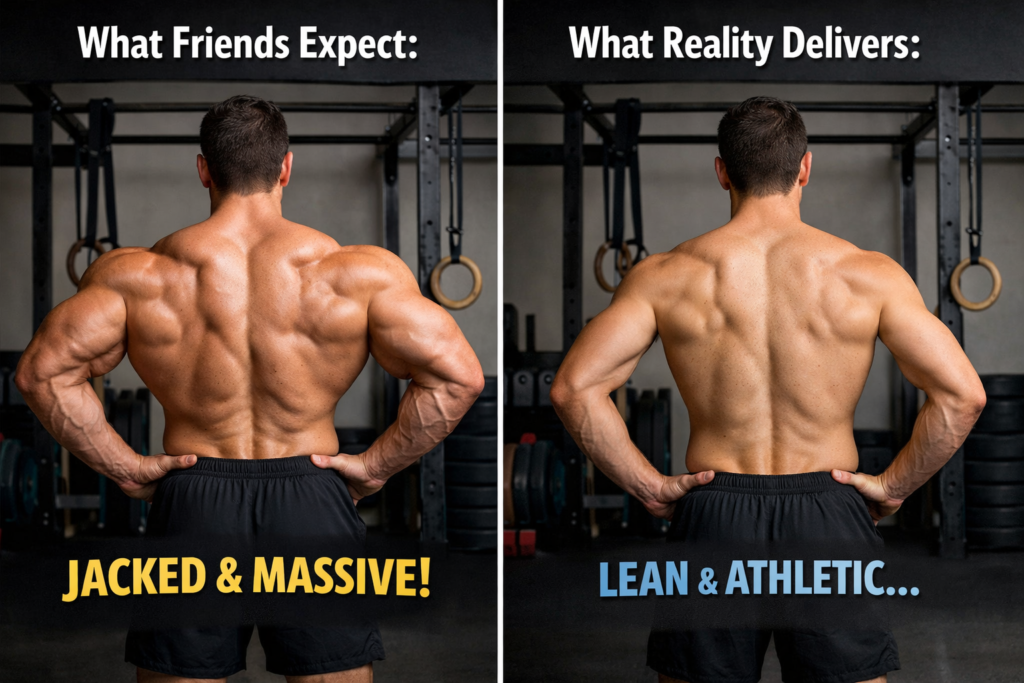

Friends would say, “You must be huge now.”

Photos would say, “You look athletic.”

My ego wanted “comic book back thickness.”

Reality delivered “lean, capable, slightly confusing.”

That gap pushed me into test mode.

Not influencer test mode.

More like: spreadsheet, tape measure, same lighting, same scale, same weekly routine.

The First Big Idea: Strength Is Not One Thing

“Strength” is a messy word.

Calisthenics strength often means relative strength plus skill.

Gym strength often means absolute force output with fewer moving parts.

Both are real.

Both are impressive.

Only one consistently screams size.

Relative strength rewards efficiency.

Efficiency is basically your body saying, “Cool, I can do this with less muscle than you think.”

That is awesome for performance.

It’s not always awesome for looking like you bench press small cars.

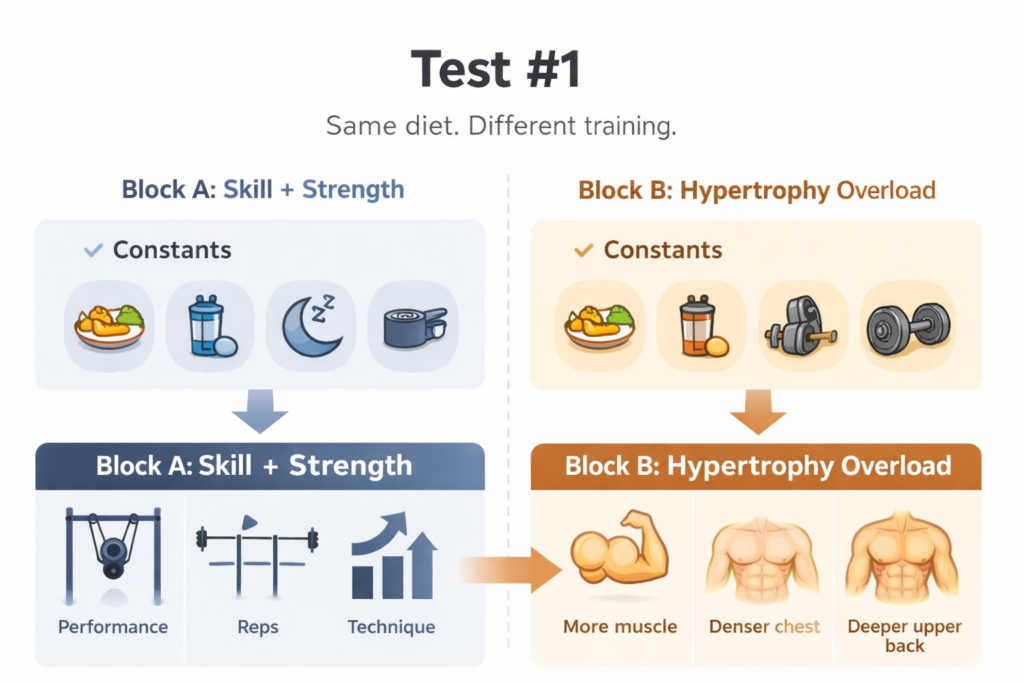

Test #1: Same Calories, Same Protein, Different Training Style

Here’s the cleanest test I ran because it removed the usual excuse.

Food stayed stable for weeks.

Protein stayed stable.

Sleep stayed stable.

Weight stayed within a tight range.

Training was the only big change.

Block A was mostly calisthenics skill + strength.

Block B was mostly hypertrophy-style overload using similar movement patterns.

So instead of random new exercises, I kept “families” consistent:

Vertical pull stayed vertical pull.

Horizontal push stayed horizontal push.

Leg work stayed leg work, even if the tools changed.

In Block A, performance jumped.

Reps went up.

Holds got longer.

Technique got smoother.

In Block B, the mirror improved faster than the skill numbers.

Arms filled out more.

Chest looked denser.

Upper back started showing depth instead of just definition.

That was the first clue.

Calisthenics was making me better faster than it was making me bigger.

Why Calisthenics Prioritizes Control Over Tissue Growth

Strength gains come from multiple places.

Muscle size is only one of them.

Neural coordination is the underrated monster in calisthenics.

That includes:

Better motor unit recruitment.

Less “wasted” tension.

Smoother joint stacking.

Cleaner leverage.

More confident force production.

Imagine two people learning the same complex movement.

One tries to overpower it with raw effort.

The other refines positioning, timing, and sequence until the movement feels almost automatic.

Both can complete the task.

Only one looks smoother doing it.

Calisthenics usually takes the second route.

Control improves before anything visibly changes.

Hypertrophy, instead, is closer to adding more material to the system so precision becomes less necessary.

More tissue solves the problem differently, not more elegantly.

The Skill Filter: When Technique Fails Before Muscle Fails

This is a huge one and people skip it because it’s not glamorous.

Muscle growth loves local fatigue.

Hypertrophy tends to happen when a target muscle approaches failure under tension.

Calisthenics frequently ends a set for a different reason:

Scapula position breaks.

Core loses line.

Elbow path becomes messy.

Balance becomes the limiting factor.

So the set ends…

…while the prime mover still had a couple reps left “in the tank.”

That means the stimulus was distributed.

The nervous system got challenged.

Stabilizers got hammered.

Skill got trained.

Prime mover hypertrophy wasn’t guaranteed.

It’s not that calisthenics can’t build muscle.

It’s that calisthenics sometimes stops you early for reasons that don’t directly equal growth.

Mechanical Tension: Hard Doesn’t Always Mean Growth-Hard

A move can feel brutal and still be a weird hypertrophy tool.

Front lever is a perfect example.

That hold feels like the universe is trying to unzip your shoulders.

But where is the tension?

It’s spread across lats, teres, core, scapular depressors, even forearms, plus constant micro-adjustments.

A heavy chest-supported row is boring by comparison.

Yet rows often grow lats faster because the tension is more direct and repeatable.

Calisthenics difficulty often comes from leverage and coordination.

Hypertrophy-friendly difficulty comes from sustained tension and fatigue in a target muscle.

Both can overlap.

They don’t always.

Time Under Tension: The Quiet Difference Between “Strong” and “Big”

In many calisthenics sessions, reps are crisp and fast.

Even controlled reps are often controlled for form, not for hypertrophy intent.

Hypertrophy work often lives in slower eccentrics, longer sets, and more burn.

That burn is not the goal by itself.

The burn is just a symptom that the muscle is doing a lot of continuous work.

In my skill blocks, I noticed something:

Sets felt demanding, but not always “muscle-full.”

A planche lean session could cook my wrists and shoulders without giving me the deep chest/triceps fatigue that dips do.

A muscle-up session could smoke coordination without leaving the biceps pumped the way curls do.

A front lever session could drain my whole system without leaving my lats feeling like they had a direct workout.

So the body got better at the skill.

Size didn’t always follow at the same pace.

Energy Cost vs Growth Signal: Burning Calories Isn’t the Same as Building Tissue

Here’s the slightly annoying truth.

Calisthenics can be metabolically expensive.

Heart rate often stays higher than expected.

Sessions feel athletic and demanding.

Recovery can feel heavier than the muscle soreness would suggest.

None of that guarantees a strong hypertrophy signal.

A large portion of the energy gets spent on stabilization and coordination.

That work is real and valuable.

It just doesn’t always tell a specific muscle to grow.

Think about walking on uneven ground versus walking uphill.

Both require effort.

Both burn energy.

Only one consistently pushes the legs to adapt by adding tissue.

Staying balanced teaches control.

Climbing forces structural change.

Muscle growth works the same way.

For size to increase, the signal has to be local, repeatable, and progressively harder.

Otherwise the body simply gets better at managing the task it already knows.

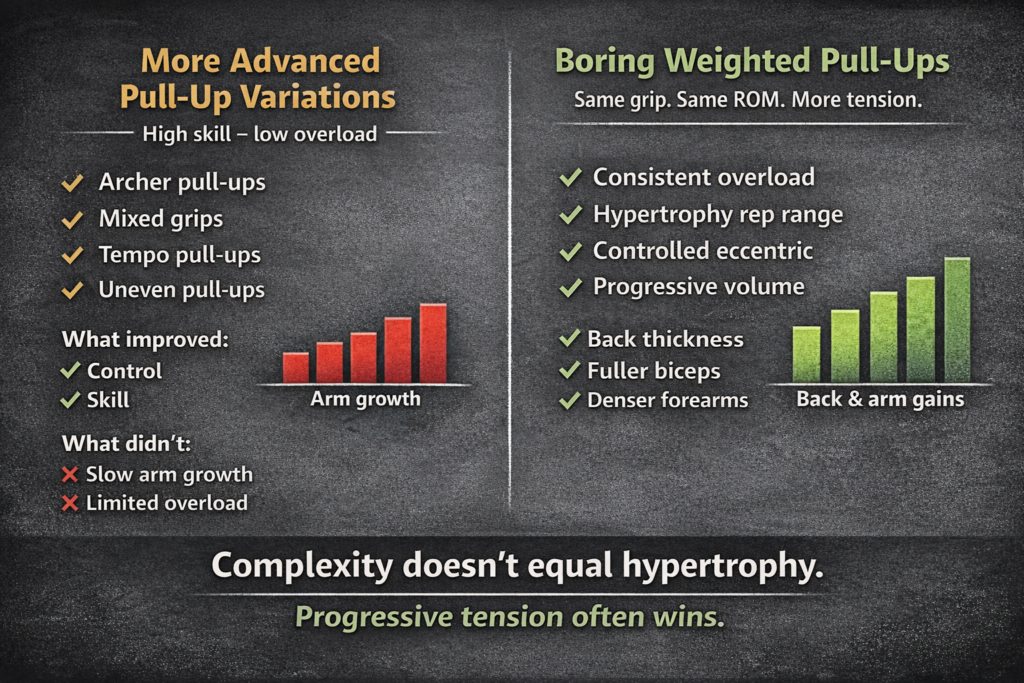

Test #2: Weighted Pull-Ups vs “More Advanced” Pull-Up Variations

This one was nerdy and honestly fun.

For a while I chased harder variations: archer pull-ups, mixed grips, tempo pull-ups, uneven pull-ups.

Those improved control and made standard pull-ups feel easy.

But arm growth was slow.

Then I ran a block with simple weighted pull-ups, same grip, same ROM, consistent overload.

Reps stayed in a hypertrophy-friendly range.

Tempo got controlled on the way down.

Volume increased gradually.

Results were clearer.

Back thickness improved faster.

Biceps looked fuller.

Forearms got denser.

The “harder variation” block made me more skilled.

The “weighted boring pull-up” block made me look more like I trained my back.

Lesson learned.

Complexity doesn’t equal hypertrophy.

Progressive tension often wins.

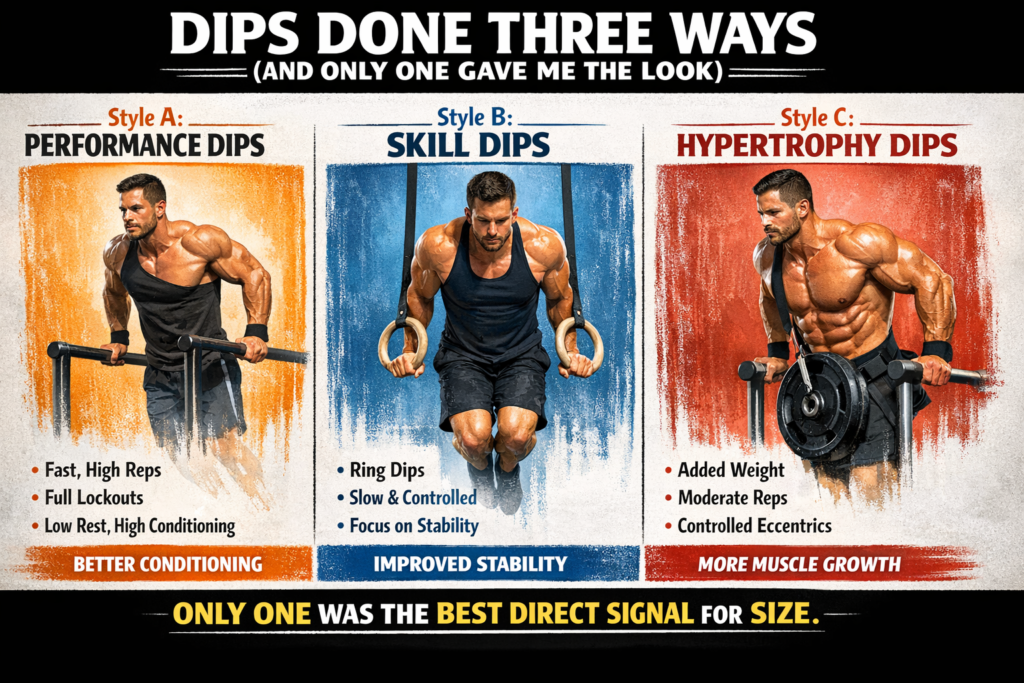

Test #3: Dips Done Three Ways (And Only One Version Gave Me the Look)

Dips can be a chest builder, a triceps builder, or a shoulder irritation builder.

So I tested three styles over time, keeping weekly sets similar.

Style A was “performance dips.”

Fast reps.

Clean lockouts.

High reps, low rest.

Great conditioning, great capacity.

Style B was “skill dips.”

Ring dips with lots of stabilization.

Slower, more controlled, more stressful overall.

Strength improved.

Stability improved.

Style C was “hypertrophy dips.”

Added weight.

Moderate reps.

Full ROM.

Controlled eccentrics.

Stop 0–1 reps shy of form breakdown.

Style C changed my chest and triceps the most.

Style B made my shoulders feel like they learned a new language.

Style A made me better at doing dips forever.

None of them were “wrong.”

Only one was the best direct signal for size.

The Size Penalty: Calisthenics Rewards Staying Light

This part is simple but powerful.

Every extra kilo is something you must lift in every rep.

So calisthenics training often selects for staying lean and efficient.

Gaining mass can even feel like moving backwards temporarily.

Pull-ups get harder.

Levers feel heavier.

Holds shorten.

That feedback loop makes people accidentally avoid bulking.

Even when calories are adequate, training intensity might shift because heavier bodyweight changes leverage and fatigue.

So the body adapts to be strong at your weight.

Not necessarily to add mass beyond what helps performance.

A gym lifter can gain 3–5 kg and still keep lifting heavier loads because the external weight can be adjusted.

Calisthenics makes you carry the upgrade everywhere.

Sometimes the body chooses efficiency over expansion.

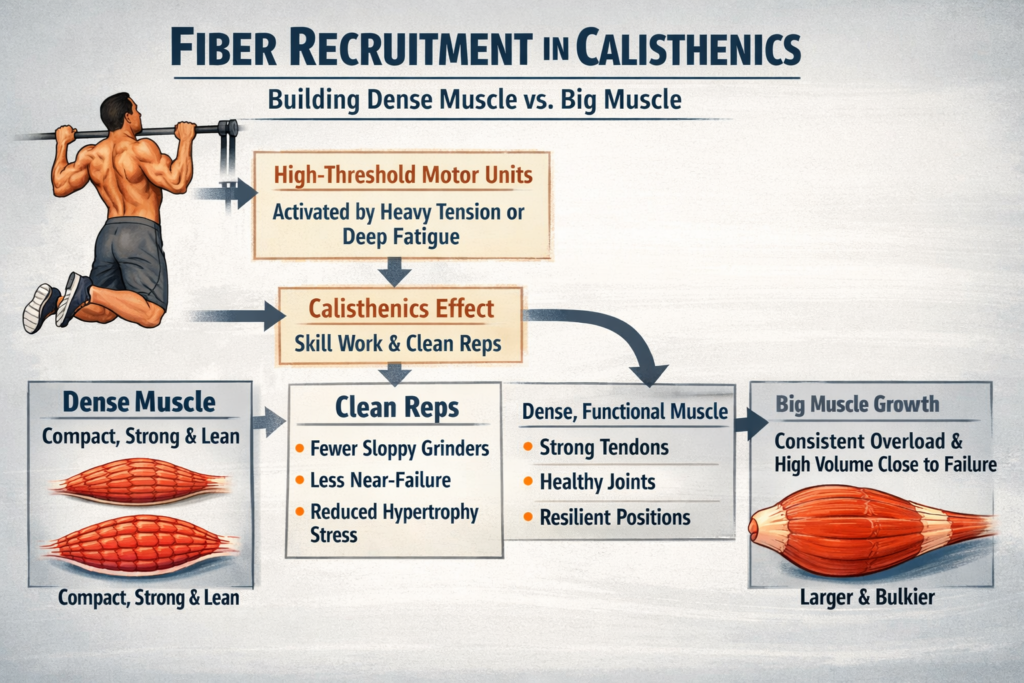

Fiber Recruitment: Why Calisthenics Often Builds Dense Muscle More Than Big Muscle

Muscle size is influenced by which fibers get hammered and how.

High-threshold motor units are growth-friendly.

They activate most reliably under heavy tension or deep fatigue.

Calisthenics activates them, yes.

But skill work can reduce the need to grind into deep fatigue.

Form improves, so reps get “cleaner.”

Clean reps are great.

Clean reps also mean fewer sloppy grinders, fewer near-failure reps, less hypertrophy stress—unless you program it intentionally.

So calisthenics can build that compact, dense look.

It often builds strong tendons, good joints, resilient positions.

Big size usually needs consistent overload plus enough volume close to local fatigue.

The Range of Motion Issue: Full ROM Isn’t Always “Full ROM”

Calisthenics has a ROM trap.

A pull-up to chin over bar is a full pull-up.

But lats often grow best with deep stretch and strong contraction through a stable path.

Many people do pull-ups with:

Limited scapular depression at the bottom.

Ribs flared, core loose.

Shoulders internally rotated.

Top position rushed.

Those reps count.

Those reps build strength.

Those reps might not maximize hypertrophy.

When I cleaned bottom position and owned the stretch, lats responded better.

When I slowed eccentrics and kept scapula controlled, back development improved.

Same exercise name.

Different stimulus.

Calisthenics doesn’t forgive lazy positions.

Hypertrophy especially doesn’t forgive them.

Load Progression: Calisthenics Has Fewer “Micro-Progressions” Than Gym Work

Gyms are unfairly convenient.

Add 1.25 kg per side.

Progress happens.

Calisthenics can jump in bigger steps.

A harder variation might be 10–20% harder, not 2–3% harder.

That makes hypertrophy programming trickier.

Hard jumps push you into low reps and skill failure.

Low reps and skill failure build strength.

Size still can happen, but volume is harder to accumulate.

Weighted calisthenics fixes this.

A dip belt is basically a “micro-progression machine” for bodyweight training.

Once I used external load as the progression tool, size became more predictable.

Where People Get Confused: “I’m Strong, So Why Aren’t My Arms Huge?”

Because the strength may be distributed.

Calisthenics strength is often whole-chain strength.

Arms contribute, sure.

Lats contribute.

Core contributes.

Scapular control contributes.

Grip contributes.

So you can become very strong at a movement without isolating a single muscle enough to force it to grow a lot.

That’s not a weakness.

That’s how compound, skill-heavy work behaves.

If the goal is size, the solution is not abandoning compounds.

The solution is making size work non-negotiable inside the system.

How I Finally Got Better Size Carryover Without Betraying Calisthenics

A simple rule changed everything once I stopped asking calisthenics to solve every problem by itself.

Calisthenics stayed the identity of the training.

Hypertrophy became the engine that supported it instead of competing with it.

That separation alone made programming clearer and results more predictable.

The week was built around two distinct layers with different goals.

Layer 1: Skill and Strength Practice

This layer focused on movement quality, not exhaustion.

Fatigue stayed intentionally low so technique could remain sharp.

Sets ended when form started to degrade, not when muscles were completely fried.

Front lever progressions worked well here because they train scapular depression, core tension, and lat engagement without chasing failure.

Execution mattered more than duration.

Shoulders stayed packed, ribs stayed down, and tension was spread through the whole body rather than forced into the arms.

Technique pull-ups also lived in this layer.

Each rep started from a dead hang with active shoulders, controlled scapular engagement, and a smooth pull toward the bar without momentum.

The goal was consistency and precision, not pump or burn.

Layer 2: Hypertrophy Overload

This layer had a completely different role and mindset compared to skill work.

Here, the goal wasn’t to “perform the movement well,” but to make the muscle work as directly as possible.

Stability became a priority because reducing variables meant amplifying the growth signal.

Load was progressive and measurable, allowing clear week-to-week verification that the stimulus was actually increasing.

Local muscle fatigue stopped being a side effect and became the main target.

Sets interrupted due to loss of balance or coordination were considered incomplete from a hypertrophy perspective.

The focus shifted toward continuous tension, controlled eccentrics, and repetitions taken close to technical failure.

Reps were meant to slow down because the muscle was tired, not because the movement was becoming unstable.

Load selection aimed for a moderate rep range, high enough to accumulate volume but low enough to demand real tension.

Rest periods existed to recover the muscle, not to “catch your breath” from a cardiovascular standpoint.

In this context, simplicity became an advantage.

Repeatable exercises, predictable movement paths, and quick setups allowed the body to understand exactly where adaptation was required.

Here, muscles could finally do real work without coordination ending the set too early.

Pulling: Skill vs Hypertrophy

Skill pulling revolved around front lever work and strict pull-up control.

These movements improved coordination, line control, and force transfer through the entire pulling chain.

Hypertrophy pulling relied heavily on weighted pull-ups.

Added load allowed progression without changing technique every week.

Execution stayed strict, with a controlled eccentric and a brief pause at the top to avoid turning the movement into momentum.

Rows complemented this work by adding horizontal pulling volume.

Chest-supported or bench-supported rows reduced lower-back fatigue and allowed the upper back to reach real muscular fatigue.

Curls played a specific role rather than an ego-driven one.

Elbow flexors were already involved in pulling, but direct curls allowed them to fatigue without grip or scapular stability becoming the limiter.

Slower eccentrics increased time under tension without forcing excessive volume.

Pushing: Skill vs Hypertrophy

Skill pushing focused on handstand work and ring support holds.

These exercises trained shoulder stability, balance, and control in overhead and deep support positions.

In handstand work, alignment mattered more than hold duration.

Hands stayed stacked under shoulders, ribs stayed down, and balance corrections stayed small and controlled.

Hypertrophy pushing relied on weighted dips as the main driver of size.

Added load created a clear stimulus for chest and triceps without instability stealing effort.

Execution stayed deep and controlled, with shoulders staying depressed and elbows tracking naturally.

Loaded or tempo push-ups extended volume while keeping joints comfortable.

Triceps extensions filled the final gap by allowing elbow extensors to reach true local fatigue without shoulder positioning becoming the weak link.

The Honest Approach to Legs

Leg training stopped pretending pistols alone were enough for size.

Pistols stayed useful for control, balance, and mobility.

Hypertrophy required load.

Weighted split squats became a staple because they allowed unilateral loading with high stability.

A long stride emphasized glutes, while a shorter stride shifted more work to the quads.

Romanian deadlifts covered the posterior chain through a controlled hip hinge and a consistent stretch under load.

Heavy step-ups added leg volume without excessive spinal fatigue, which helped overall recovery.

Leg size finally responded once resistance became unavoidable.

No shame involved.

Just clarity.

Why This Structure Finally Worked

Skill work kept movement quality improving without draining recovery.

Hypertrophy work delivered a clear and localized growth signal.

Each layer respected its role instead of trying to do everything.

Calisthenics remained the language of movement.

Hypertrophy became the tool that made that movement visible in the mirror.

That balance solved the size carryover problem without abandoning the original training identity.

Practical Fix #1: Put Your “Size Sets” First Sometimes

Skill-first training is logical.

Fresh nervous system improves technique.

But hypertrophy sometimes benefits from being first too.

So I alternated phases.

Some blocks started with skill.

Some blocks started with hypertrophy.

When size was the priority, hypertrophy work went earlier in the session.

Performance dipped slightly in the skill work after.

But size responded better.

That trade was worth it for certain phases.

A balanced approach isn’t always “same priority always.”

Sometimes the priority rotates.

Practical Fix #2: Choose Variations That Reduce Skill Failure

If balance ends the set, the muscle didn’t truly fail.

So I used stable versions for hypertrophy sets.

Rings are amazing, but rings can steal growth volume when stability dominates.

So I kept ring work as skill/stability.

For hypertrophy, I used parallel bars, weighted dips, stable pull-up bars, chest-supported rows.

The goal was not “easier.”

The goal was “more direct.”

Direct work is boring in the best way.

Boring work grows muscle.

That’s the deal.

Practical Fix #3: Track the Right Metrics (Tape Beats Ego)

Strength metrics are exciting.

Size metrics are humbling.

So I measured simple things consistently:

Bodyweight averages.

Upper arm circumference relaxed and flexed.

Chest around nipple line.

Shoulders around widest point.

Photos with same lighting and distance.

Then I connected them to training blocks.

Skill blocks improved numbers like holds and reps.

Hypertrophy blocks improved tape and photos more reliably.

Seeing that pattern repeatedly killed confusion.

The body wasn’t ignoring effort.

The body was responding to the type of effort.

What This Means If Calisthenics Is the Main Goal

Calisthenics can build an incredible physique.

But expecting automatic size from skill strength is like expecting a racing sim to build your car’s engine.

The sim improves your driving.

The engine still needs a wrench.

So if calisthenics performance is the priority, size might come slower.

That’s fine.

That’s honest.

If aesthetics is also a priority, targeted hypertrophy work has to be added intentionally.

Not as an afterthought.

Not as “maybe curls at the end if I feel like it.”

More like: “This is part of the system.”

| The Real Answer (compressed) |

|---|

| Calisthenics strength doesn’t always translate to size.

The system is designed to reward efficiency, leverage mastery, and whole-chain coordination. Hypertrophy, instead, rewards repeated direct tension and local muscle fatigue. Both adaptations can exist at the same time. They just don’t appear in equal amounts by default. |

Final Thoughts

Feeling strong is addictive.

Watching skills improve feels like leveling up in real life.

Then the mirror asks for a different kind of payment.

That doesn’t mean calisthenics “fails.”

It means the body is smarter than the slogans.

So if size matters, give your muscles a clearer reason to grow.

Add weight.

Add stable hypertrophy sets.

Add controlled eccentrics.

Add enough volume close to local fatigue.

Keep the fun skills too.

Keep the identity.

Just stop expecting a single tool to build every outcome automatically.

A system that builds strength and size exists.

It’s not mysterious.

It’s just deliberate.