Bodyweight training is the “free lunch” of fitness.

No commute.

No fancy machines.

No mystery attachments that look like medieval torture devices.

Just you, gravity, and a floor that judges you silently.

And for a long time, that’s enough.

You can build real muscle.

You can get strong.

You can develop joints, tendons, and coordination that carry over to almost everything.

Then one day, progress slows down.

Not because bodyweight “stops working.”

It slows down because the easiest ways to create progressive overload start running out.

At that point, external load becomes less of a betrayal… and more of a tool.

Like adding RAM to a computer instead of blaming the browser for existing.

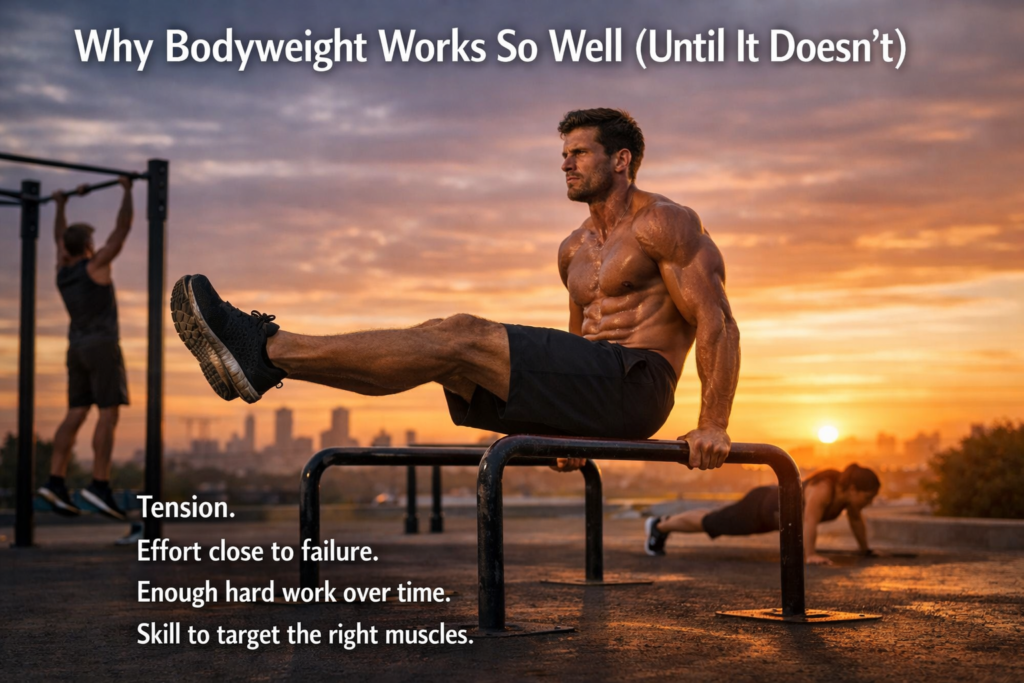

Why Bodyweight Works So Well (Until It Doesn’t)

Progress happens when training gives your body a reason to adapt.

That reason is usually one or more of these:

- More mechanical tension.

- More effective reps near failure.

- More total hard work over time.

- Better skill and coordination so the target muscles finally do their job.

Bodyweight training can deliver all of that.

Especially in the beginner and intermediate stages.

Push-ups become harder variations.

Pull-ups become cleaner and stricter.

Squats become deeper and more controlled.

Tempo gets slower.

Range gets bigger.

Form becomes less “survival mode.”

The issue is not that your body stops adapting.

The issue is that your menu of “next hard thing” shrinks.

Eventually you hit a point where making an exercise harder starts feeling like:

“Should I add load, or should I invent a new circus trick?”

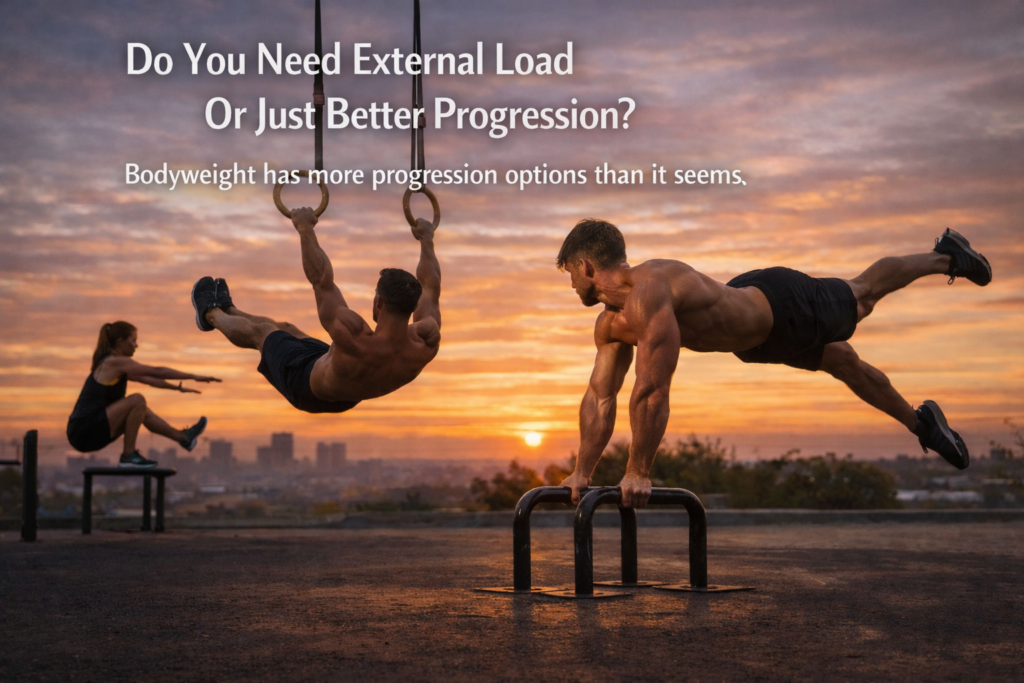

The Real Question: Do You Need External Load, Or Just Better Progression?

Before adding weight, it helps to check if you already have “free” progression options left.

Bodyweight has a lot of hidden difficulty knobs.

Here are the big ones that often get ignored:

- Range of motion: deeper, longer positions usually change the game.

- Tempo: slower eccentrics, pauses, and long isometrics increase tension without changing equipment.

- Stability: rings, parallettes, deficit work, single-leg, single-arm assistance.

- Leverage: moving hands, feet, or body angle changes load distribution dramatically.

- Density: same work in less time, more quality reps, tighter rest control.

If those levers are already maxed out, external load starts making sense.

If those levers are still wide open, you may not need weight yet.

The point isn’t to avoid weight like it’s a villain.

The point is to earn it, so the weight actually solves a problem instead of distracting from one.

The Clearest Sign You’ve Outgrown Pure Bodyweight: You’re Too Efficient

This is the funny part.

The better you get, the less stimulus a standard movement gives you.

A set of push-ups used to be a life event.

That efficiency is good.

It means your nervous system learned the skill.

It also means your muscles aren’t being challenged enough for growth, unless you scale difficulty.

A simple rule works well here:

If you can do high reps with clean form and still repeat that performance week after week, the stimulus is probably capped.

Not “no results,” but “slow results.”

Slow progress is still progress, but it may not be progress you enjoy.

Practical Thresholds: When External Load Becomes the Smart Option

Numbers aren’t magic, but they are useful.

Here are realistic checkpoints where adding load often becomes the simplest path forward.

For pushing strength and muscle

If you can do 20–30 strict push-ups with full control, standard push-ups stop being an efficient main lift.

If you can do 15–25 deep ring push-ups with solid stability, the next bodyweight steps may become very technical.

If you can do 10–15 clean dips with full depth and no shoulder discomfort, adding weight is often safer and more scalable than chasing extreme dip variations.

For pulling strength and muscle

If you can do 10–15 strict pull-ups with a dead hang and no momentum, weighted pull-ups are usually the cleanest upgrade.

If you can do 15–20 strict chin-ups while keeping ribs down and elbows controlled, you’re basically asking for a heavier problem.

If rows feel easy no matter how you angle them, load helps you keep progressing without turning the movement into a yoga pose.

For legs (the most common plateau zone)

Lower body is where bodyweight hits its limit first for many people.

If you can do 20+ deep single-leg squats to a box per side with control, the next jump in difficulty can be awkward without load.

If split squats and lunges feel like conditioning more than strength work, external load is often the missing piece.

If hamstring work is mostly “bridges forever,” loading hinges or adding weight to curls becomes a practical upgrade.

These thresholds don’t mean bodyweight is done.

They mean your current variations may not be the best “return on effort” anymore.

The Two Types of Plateaus That Tell Different Stories

Not every plateau means “add weight now.”

Two different stalls exist.

Plateau Type A: Skill bottleneck

Reps aren’t improving because the movement is shaky, inconsistent, or technique-limited.

Rings wobble.

Scapula does weird things.

Depth changes every rep like a surprise plot twist.

That kind of plateau wants practice, not plates.

External load can even make it worse.

Plateau Type B: Stimulus bottleneck

Form is solid.

Reps are consistent.

Recovery is good.

Progress is still flat for weeks.

That plateau usually wants more tension.

External load is a direct way to get more tension without turning training into an engineering degree.

External Load Isn’t Just “More Weight” (It’s Better Control of Progress)

The biggest advantage of weight is not ego.

It’s precision.

Bodyweight progression sometimes jumps in big steps.

One variation is too easy.

The next variation is too hard.

That gap can stall you for months.

External load fills the gap.

You can add 2.5–5 pounds and keep the movement the same.

You get progressive overload without rewriting your entire exercise library.

That’s not boring.

That’s efficient.

Efficiency is very underrated in fitness culture.

The “Circus Trick” Trap: When Harder Variations Stop Being Better

Some advanced bodyweight variations are incredible.

Planche progressions, one-arm pulling work, levers, and strict ring strength are legit.

They are also very skill-heavy.

Skill-heavy doesn’t mean “bad.”

Skill-heavy means muscle growth may no longer be the main adaptation.

At a certain point you’re training:

- technique,

- balance,

- tendon tolerance,

- joint angles,

- and a lot of neurological coordination.

All good things.

But if the goal is mainly hypertrophy or general strength, external load often gives you more direct payoff.

A Simple Decision Test: Add Load If These Four Boxes Are Checked

Use this quick checklist.

External load becomes the smart move when:

- Technique is consistent.

- You can get close to failure without form collapsing.

- The next bodyweight progression feels like a giant leap, not a step.

- Weekly progress has stalled for 3–6 weeks despite good sleep and food.

If those boxes are checked, adding load is not “giving up on calisthenics.”

It’s continuing calisthenics with a better dial.

What Kind of External Load Should You Use

External load doesn’t have to mean a full gym membership and a rack that costs more than a scooter.

Here are the most practical options.

Weighted vest

Great for push-ups, dips, pull-ups, step-ups, and carries.

The load distribution is stable.

It keeps your hands free.

It’s the “plug-and-play” option.

Dip belt

Excellent for dips and pull-ups.

It keeps the movement natural.

It scales heavy over time.

It feels very “strength focused.”

Backpack loading

Cheap and effective.

Books, water bottles, bags of rice, whatever behaves.

The downside is comfort and load shifting.

The upside is you can start today.

Dumbbells or kettlebells

Best for legs, hinges, rows, loaded carries, and unilateral work.

This is the easiest way to make lower body training truly progressive without turning single-leg work into endless endurance.

Resistance bands

Good for accommodating resistance, assistance, or higher-rep finishers.

Bands can be useful, but they’re harder to standardize for strict progression.

They shine when used as a tool, not the main metric.

How to Add Load Without Losing the “Bodyweight Feel”

Some people worry that adding weight turns bodyweight training into regular lifting.

That only happens if you abandon the bodyweight principles that made you better.

Keep these habits:

- Full range of motion.

- Clean reps.

- Control on the way down.

- Stable positions.

- Strong scapular mechanics.

External load should make those qualities more meaningful, not replace them.

A weighted pull-up done with control still feels like calisthenics.

It just feels like calisthenics with a harder boss fight.

Programming Options That Actually Work

You do not need a complicated plan.

You need a repeatable plan.

Here are three simple setups that fit most goals.

Option 1: Keep the movement, add small weight

Pick a main movement.

Add load gradually.

Stay in a rep range like 4–8 or 6–10.

Add weight when you hit the top of the range with clean reps.

This is the cleanest strength progression.

Option 2: Heavy first, bodyweight volume after

Start with weighted pull-ups or weighted dips.

Do a few strong sets.

Then follow with bodyweight sets for volume and quality reps.

This builds strength and keeps skill sharp.

Option 3: Alternate phases

Spend 4–8 weeks focusing on weighted strength.

Then spend 4–8 weeks focusing on bodyweight skill and volume.

This keeps training fresh and protects joints from constant high intensity in the same patterns.

Variety is not randomness.

Variety is planned change that still respects progression.

Common Mistakes When People Start Adding Load

A few things can turn a smart upgrade into a cranky joint situation.

Jumping load too fast

Tendons adapt slower than muscles.

That’s not motivational.

That’s biology.

Small jumps keep elbows and shoulders happier.

Letting form degrade because “it’s heavier now”

Heavier weight does not excuse ugly reps.

Ugly reps are still ugly reps.

They just happen with more force going through your joints.

Turning every set into a max effort

Training hard is good.

Training at your maximum every session is not a personality trait worth keeping.

Leave one or two reps in reserve often.

Progress comes from consistency, not drama.

Ignoring lower body loading

Upper body calisthenics gets all the attention.

Legs often get stuck doing high-rep sets forever.

A pair of dumbbells can save you years of pretending pistol squats are the only path.

What If the Goal Is Muscle Growth, Not Max Strength

Hypertrophy has a simple reality.

Muscle likes tension plus enough volume close to failure.

Bodyweight can do that.

External load can do that more predictably.

If you’re chasing growth, external load becomes useful when:

- bodyweight sets drift into very high reps,

- fatigue becomes mostly cardiovascular,

- and the target muscle stops being the limiting factor.

If your push-ups end because lungs are on fire but chest still feels undertrained, load helps.

If your split squats end because balance fails before the quads get real tension, load helps.

If your pull-ups are clean but can’t get harder without weird form compromises, load helps.

Safety Notes That Matter More Than They Sound

Weighted calisthenics is safe when it’s respected.

It becomes sketchy when people treat it like a shortcut.

Here are practical guardrails:

- Warm up joints with easy reps first.

- Use smaller increments than you think you need.

- Stop sets when form changes, not when motivation fades.

- Deload every few weeks if joints feel “hot” or achy.

Pain is not a badge.

Pain is data.

Training is the skill of listening without panicking.

So… What’s the Point Where You “Need” External Load

You “need” external load when bodyweight progression stops being the best tool for the job.

That moment usually looks like this:

- Standard variations are too easy for effective strength or hypertrophy.

- Advanced variations are too technical to scale smoothly.

- Progress is flat even though effort, sleep, and food are solid.

External load is not a surrender.

External load is a way to keep the simple things simple.

You can still be a bodyweight athlete.

You can still train at home.

You can still stay joint-friendly and athletic.

You’re just adding a dial that lets you progress in smaller, smarter steps.

If bodyweight training is the game engine, external load is the expansion pack.

Nothing about your identity has to change.

Only your options get better.

And that’s the whole point.