Jumping rope felt like the fitness version of plain rice cakes.

Technically acceptable.

Emotionally… a little sad.

Then I started treating it as a serious part of my calisthenics routine instead of simple “cardio garnish,” and everything became strangely useful, strangely fast.

In a subtle way.

More like a “why are my calves starting to speak up?” kind of feeling.

This is a real, practical experience built on concrete attempts, small embarrassing mistakes, and gradual adjustments until I found a setup that made sense.

A clear before and after in how my body handled calisthenics sessions.

Why Jumping Rope Even Belongs Near Calisthenics

Calisthenics is bodyweight training.

That means the body is the equipment, the engine, and sometimes the impatient toddler inside the shopping cart.

Strength matters, but coordination and fatigue management matter just as much.

Jumping rope fits because it’s a coordination-heavy, rhythm-based, low-equipment way to build work capacity without turning your joints into a complaint department.

Running can do that too, sure.

Yet rope has a special advantage: it forces timing.

Foot strike happens under you, not way out in front, and the “bounce” becomes a skill instead of just impact.

That skill carries into calisthenics faster than people expect.

Push-ups feel smoother when the trunk is used to staying stiff while something repetitive happens.

Pull-ups feel cleaner when breathing doesn’t immediately turn into a soap opera.

Leg work feels less dramatic when ankles and feet stop acting like they’re made of dry spaghetti.

What Changed When Rope Became a Real Part of My Routine

At the beginning, rope was “warm-up entertainment.”

A few minutes, then straight into pull-ups, dips, push-ups, and some leg work.

Breathing would spike fast, shoulders would get tight fast, and I’d start bargaining with the universe during higher-rep sets.

Rope started to shift things in three ways that were easy to notice.

First, the heart rate got “less panicky” during calisthenics volume.

Not lower, just more controllable.

Second, the feet and calves stopped feeling like fragile glass during jumping and landing drills, like squat jumps or broad jumps.

Third, my warm-up got simpler, because rope covered a lot of “get the system online” work in one shot.

That third point is underrated.

Most warm-ups fail because they’re either too boring or too complicated.

Rope is neither, once the basics click.

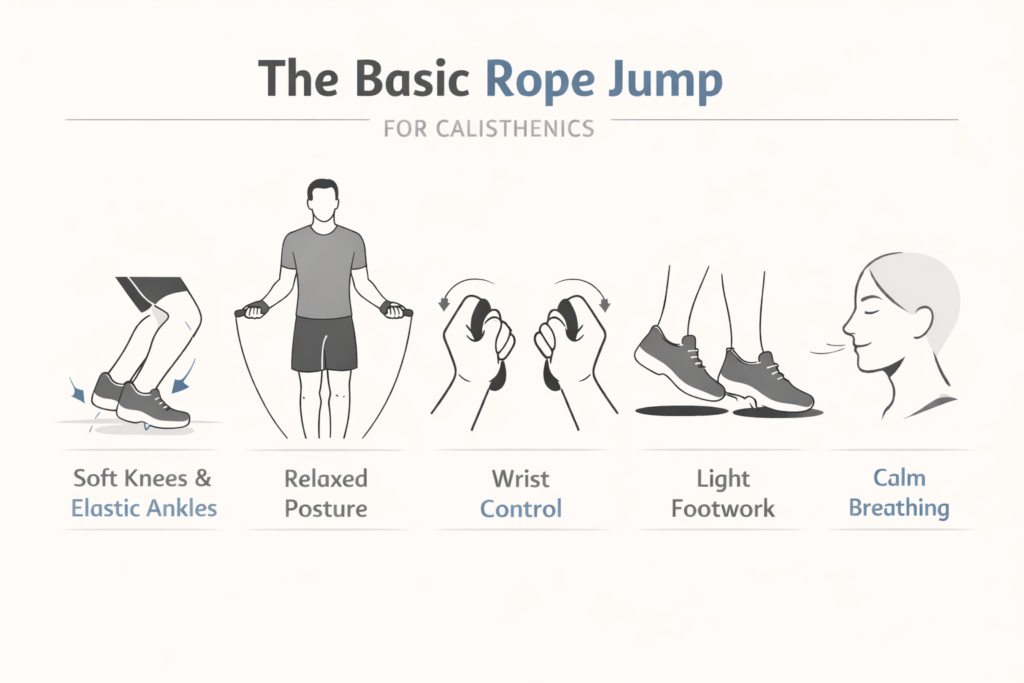

The Basic Rope Jump That Actually Transfers to Calisthenics

A lot of people think rope is all about fancy footwork.

Cool, but unnecessary at first.

The foundation is the basic two-foot bounce.

That bounce should feel like a quiet spring, not a dramatic leap.

Knees stay soft, meaning they bend a little to absorb impact.

Ankles do most of the work, but not in a stiff, locked way.

Think “elastic,” like a basketball gently dribbling itself.

Elbows stay close to the ribs, because the rope is turned by the wrists, not by helicopter arms.

Wrists make small circles, like turning two tiny doorknobs quickly.

Shoulders should not creep up toward your ears.

If traps start screaming, the arms are doing too much and the wrists are doing too little.

Landing should happen on the balls of the feet, with the heel kissing the floor lightly after.

That heel contact matters, because it spreads force and keeps calves from taking every bill in full.

Breathing stays calm, nasal if possible, because rope is partly a “nervous system relaxation” drill disguised as cardio.

When breathing turns chaotic, form gets sloppy fast, and sloppy rope is basically a toe-whip delivery service.

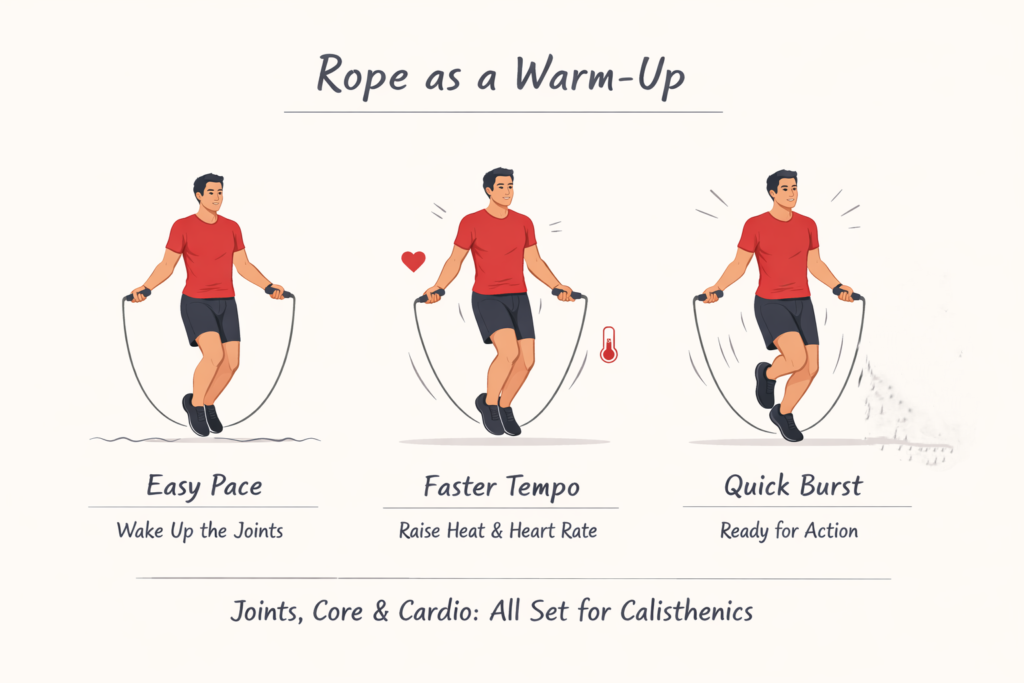

Rope as a Warm-Up: The Best Way I Found to Use It

Using rope as a warm-up sounds obvious.

Still, doing it well is not just “jump until warm.”

I started treating it like a ramp, not a punishment.

A gentle pace first, because the goal is to wake up joints and coordination.

Then a slightly higher rhythm to raise temperature and breathing.

After that, a short burst that feels “snappy,” because that bridges nicely into explosive calisthenics work like dips, push-ups, pull-ups, and transitions.

What surprised me was how much less joint stiffness I felt when rope came before upper-body work.

Shoulders didn’t feel “cold” in the first sets.

Wrists felt more awake, especially on push-ups and planche-lean style positions where the hands take real load.

Ankles felt less cranky during leg movements, especially when I later added pistol squat practice and jump variations.

That whole-body readiness is exactly what calisthenics needs, because calisthenics is not isolated-machine training.

Everything is connected, even when you’re pretending it isn’t.

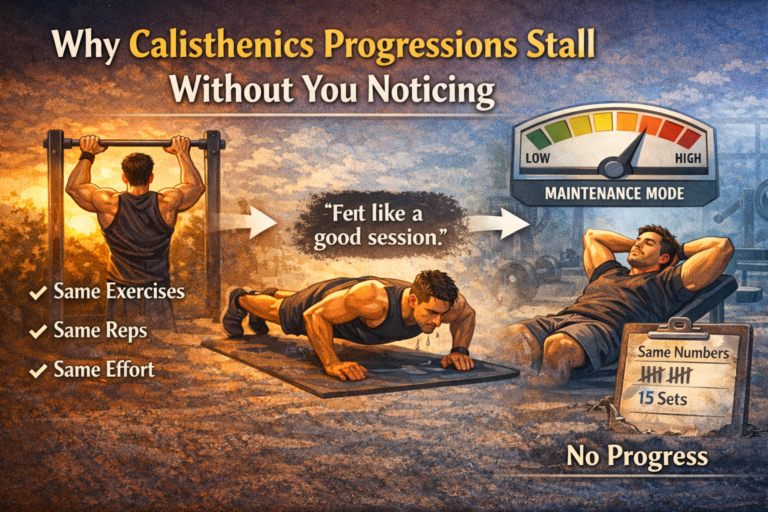

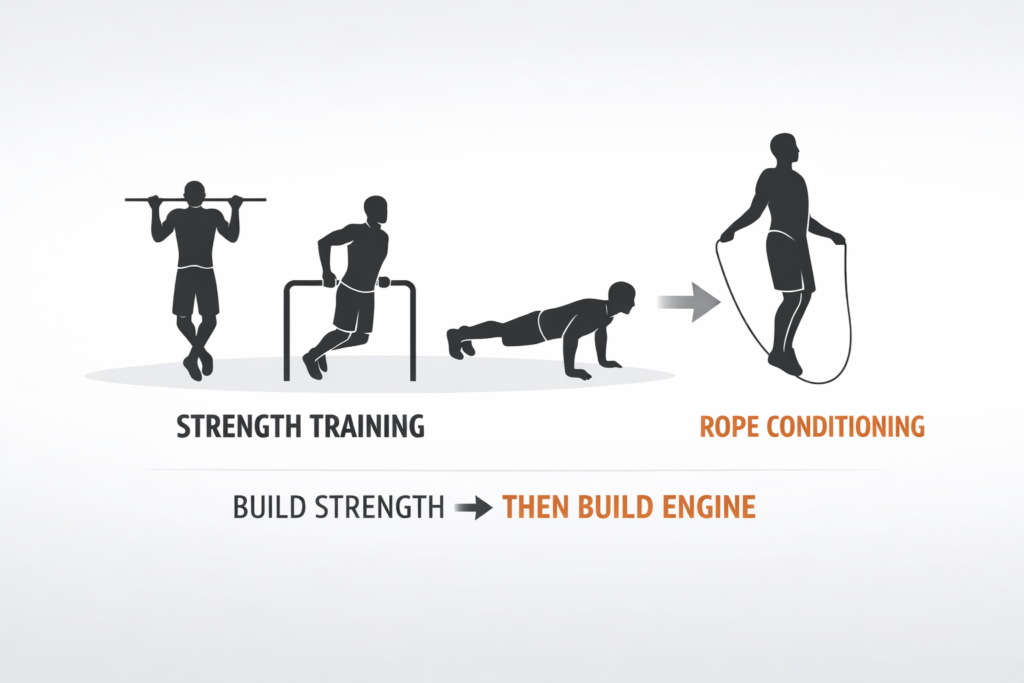

Rope as Conditioning Without Ruining Your Strength Work

Calisthenics can be strength training, skill training, and conditioning all at once.

That’s convenient, but also risky, because fatigue sneaks in and quietly sabotages form.

Rope gave me a conditioning tool I could control better than “just add more reps.”

When conditioning came only from adding reps, technique degraded.

Hands would slip, scapula control would fade, and I’d finish feeling cooked but not better.

Rope let me keep strength work cleaner while still building endurance.

The key was placement.

Putting rope after the main strength portion worked best for me.

Energy went into quality pull-ups, dips, and pushing first.

Then rope became the “engine builder” at the end, like the cooldown that still does something.

That approach kept skill and strength from turning into sloppy survival sets.

Conditioning still improved, but without turning my pull-ups into a sad interpretive dance.

How Rope Helped My Pull-Ups and Dips Without Touching a Bar

This is the part that sounds suspicious until you feel it.

Pull-ups and dips are not just about muscles.

They’re about trunk stiffness, breathing rhythm, and recovery between sets.

Rope pushed those systems in a simple, repeatable way.

During rope work, the trunk has to stay stable while the feet do repetitive impacts.

That’s basically “core endurance” without lying on the floor doing endless crunches.

Breathing under a steady rhythm also teaches control.

Pull-ups get dramatically harder when breathing is chaotic, because the upper body tightens up and the ribcage stops moving well.

Rope forced me to learn a calmer rhythm under stress.

Then that calmer rhythm showed up in my sets.

Rest times became more predictable, too.

Recovery between sets improved, because the heart rate didn’t spike as wildly.

A calmer cardiovascular response meant less “I’m dying” drama between sets, and more “I’m tired but functional.”

That’s a big difference in calisthenics.

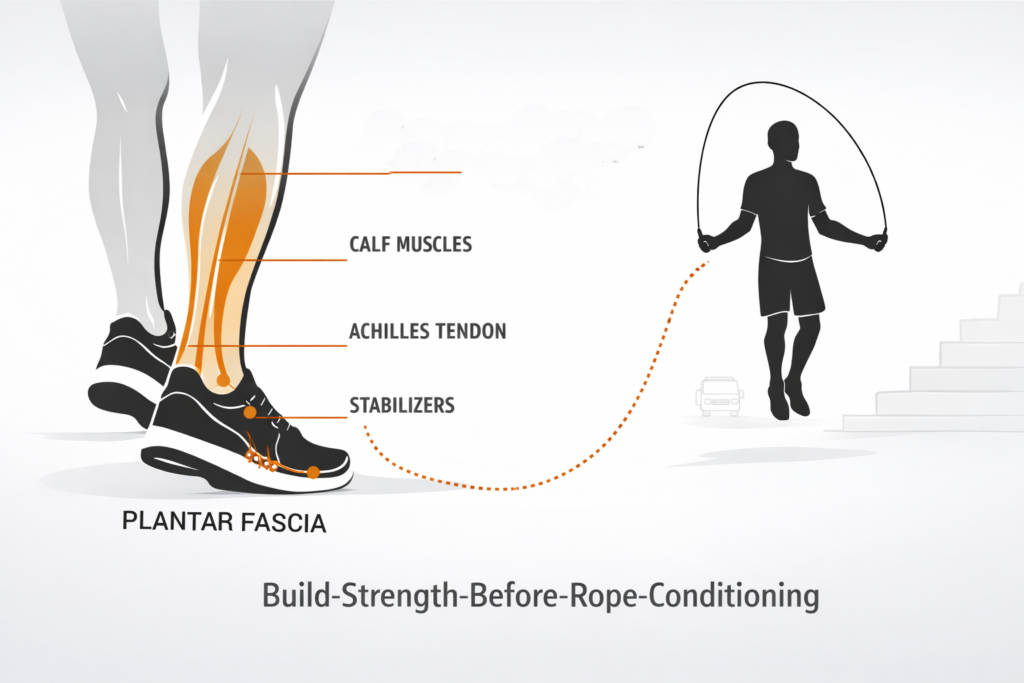

The Sneaky Foot and Ankle Benefits Nobody Mentions Enough

Calisthenics people talk about shoulders, elbows, and wrists all day.

Feet rarely get invited to the conversation.

Then someone tries pistol squats, jumping drills, or even just high-volume walking lunges, and suddenly the feet file a formal complaint.

Rope builds tolerance in the foot-ankle complex.

That means the plantar fascia, Achilles tendon, calf muscles, and all the little stabilizers in the foot start learning how to handle repeated loading.

Done gradually, that’s a gift.

Rushed aggressively, that’s a fast track to shin splints and Achilles irritation.

My own biggest shift was simply feeling “less fragile” during anything involving bouncing or landing.

Stairs felt easier after long sessions.

Jogging for a bus stopped feeling like an emergency calf workout.

That’s not glamorous, but it’s real-life athleticism.

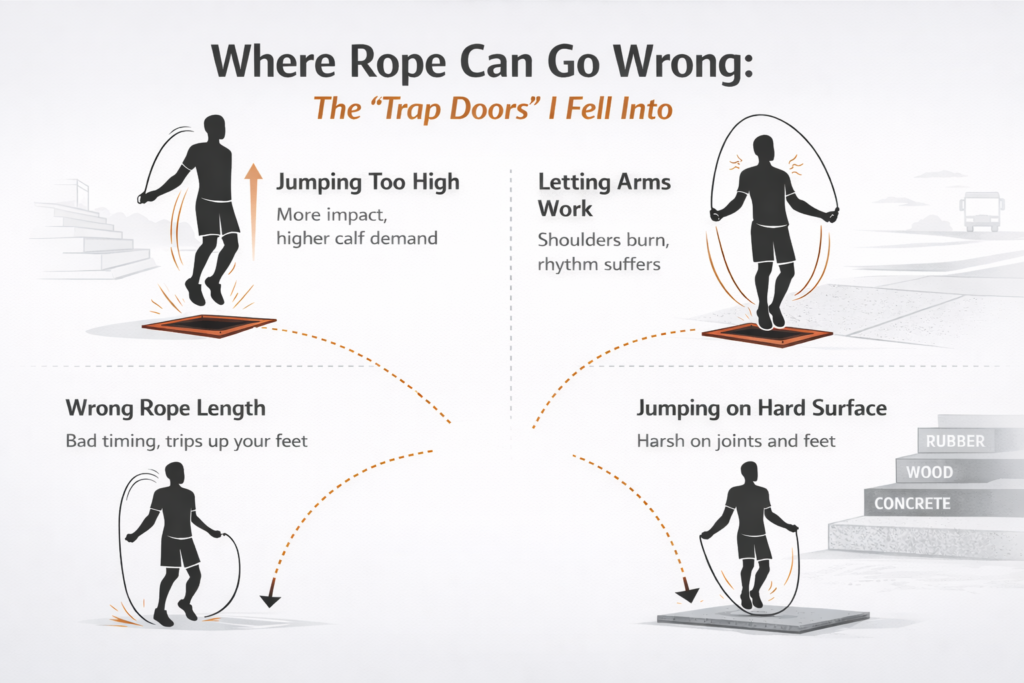

Where Rope Can Go Wrong: The “Trap Doors” I Fell Into

Rope looks simple, so it invites overconfidence.

Overconfidence is cute until the body bills you for it.

One trap door is jumping too high.

High jumps increase impact and calf demand, and they don’t improve rhythm faster.

A small bounce is the whole point.

Another trap door is letting arms do the work.

When shoulders start burning, wrists are being lazy.

Form drifts, rope speed gets inconsistent, and trips happen more often.

A third trap door is choosing a rope that’s the wrong length.

Too long makes the rope slap the floor and forces weird timing.

Too short makes you jump higher and tense up.

A fourth trap door is doing rope on a surface that’s too hard, too soon.

Concrete is honest, but brutally honest.

Joints usually prefer a slightly forgiving surface, like rubber gym flooring or wood.

Shoes matter too.

Minimal shoes can be fine, but only if calves and feet are ready.

Cushioned trainers can reduce impact early on, but sometimes they make timing feel “mushy.”

My sweet spot was a stable trainer with decent forefoot feel, not a marshmallow.

How to Pick the Right Rope Length

Rope length is not a spiritual journey.

It’s a practical setup detail.

A simple starting point is stepping on the center of the rope with one foot and pulling the handles upward.

Handles should reach roughly around the lower chest area for most people as a baseline.

If the rope keeps clipping toes even with calm jumps, it might be too short.

If the rope slaps the floor loudly and feels delayed, it might be too long.

Adjustments are normal.

Beginners often benefit from slightly longer, because timing is still learning.

As rhythm improves, a slightly shorter rope often feels smoother and faster.

Handle style matters too.

Light, smooth handles help speed and wrist control.

Heavy handles can feel good for shoulder engagement but might encourage using the arms too much.

For calisthenics support work, lighter handles usually win.

Jumping Rope Techniques That Actually Make Sense for Calisthenics

Once basic bouncing felt comfortable, adding small variations gave me more transfer without turning it into a circus act.

The first useful variation is the alternating-foot step.

Instead of bouncing with both feet, one foot taps down, then the other, like a gentle jog in place.

That reduces calf strain and spreads work across ankles and hips.

Coordination improves, and fatigue becomes more sustainable.

The second useful variation is the “high knees” version, but done modestly.

That’s not about sprinting.

It’s about bringing the knee a bit higher while keeping posture tall, which makes the trunk work harder and raises heart rate quickly.

The third useful variation is the side-to-side micro shift.

Feet hop slightly left and right while maintaining the same rope rhythm.

That challenges ankle stability and changes loading patterns, which is useful if straight bouncing makes shins angry.

None of these require double-unders.

Double-unders are cool, but they’re not mandatory for calisthenics synergy.

They also spike intensity fast, which can steal recovery from strength work if used carelessly.

How I Fitted Rope Into a Calisthenics Session Without Turning It Into Cardio Hell

A calisthenics workout has a main job.

That main job might be pull-up strength, dip strength, handstand practice, or leg strength.

Rope should support that job, not hijack it.

When I wanted rope to help the session, I used it lightly at the start and more deliberately at the end.

At the start, rope was about readiness.

At the end, rope was about conditioning.

On days where the main work was already high volume, rope stayed conservative.

On days where the main work was more skill-based, like handstand drills or controlled tempo work, rope could be slightly more ambitious.

That simple rule kept fatigue from creeping into the wrong place.

Calisthenics skills demand freshness.

Rope demands rhythm.

Freshness plus rhythm is a good combo.

Fatigue plus frustration is not.

Jump Rope Progression: Why Timing Matters More Than Speed Early On

Safe progress comes from patience, not from rushing the process.

Early on, the priority is clean, repeatable timing, not moving faster.

Short, clean rounds beat long, messy ones.

Calves and shins need time to adapt, because tendons adapt slower than muscles.

That means the body can feel fine while the connective tissue is quietly falling behind.

If shins start aching, that’s a warning light, not a challenge.

A quick fix is lowering jump height, using alternating-foot steps, and reducing total volume.

Surface choice helps too.

Rubber flooring can be a joint-saver early on.

Rope work should finish with the feeling that more was possible.

Stopping while still “okay” is what builds tolerance.

Grinding until form collapses is what builds soreness and regret.

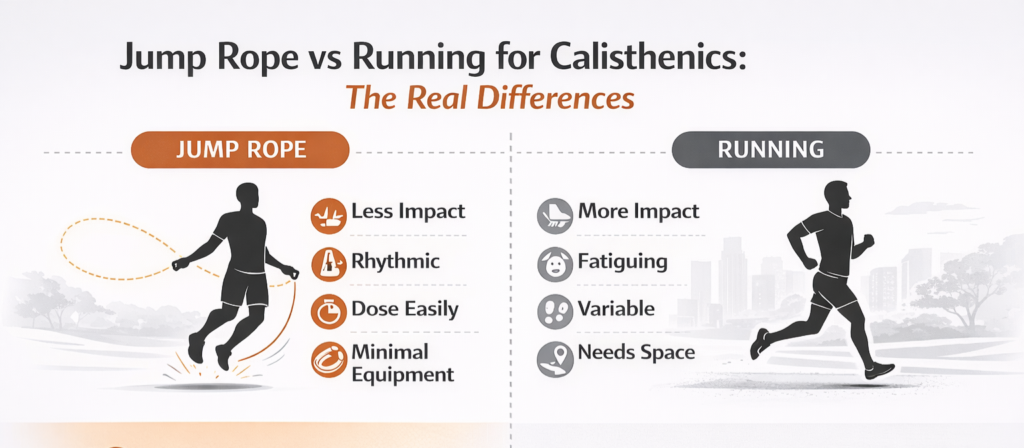

Jump Rope vs Running for Calisthenics: The Real Differences

Running is great conditioning, but it’s not always calisthenics-friendly in high amounts.

Impact is higher, stride mechanics vary, and fatigue can linger in the legs and feet.

Rope has impact too, yet it’s more vertical, more controllable, and easier to dose in small chunks.

Rope also trains rhythm and coordination more directly.

Running trains endurance, but not necessarily timing under repeated micro-contacts.

For someone doing a lot of upper-body calisthenics, rope can build conditioning without adding long sessions that eat recovery.

For someone already running regularly, rope might be redundant, unless coordination and foot stiffness are weak points.

Both tools work.

Rope just fits the “minimal equipment, high carryover” mindset that makes calisthenics appealing in the first place.

When Jumping Rope Might Not Be the Best Choice

Some bodies don’t love rope at first.

If Achilles tendons are irritated, rope can aggravate them.

If plantar fasciitis is active, repeated forefoot loading can be too much.

If knees are angry, high-impact bouncing might be the wrong entry point.

That doesn’t mean rope is banned forever.

It means the entry point needs to change.

Lower-impact options like brisk incline walking, cycling, rowing, or shadow boxing can build conditioning while foot tissues calm down.

Later, rope can return gradually, starting with alternating-foot steps and small volume.

Pain is not a badge.

Pain is information.

Calisthenics already asks a lot of joints, so conditioning should not become an extra injury hobby.

What Jumping Rope Gave Me That I Didn’t Expect

The biggest surprise was not weight loss or some dramatic endurance flex.

The biggest surprise was how much calmer training felt.

Transitions between exercises got easier.

Breathing stayed under control longer.

Warm-ups stopped feeling like a complicated ritual.

Feet and calves became more resilient without needing fancy rehab routines.

Rope also made workouts feel more playful, which matters more than people admit.

Consistency loves simplicity.

Simplicity loves tools that work.

Jumping rope is one of those tools, when used with respect instead of bravado.

Closing Thoughts: Rope Doesn’t Replace Calisthenics, It Supports It

Jumping rope doesn’t need to be the star of the show.

It works best as the reliable supporting character who shows up, does the job, and doesn’t demand a spotlight.

Used smartly, it builds coordination, conditioning, and lower-leg durability in a way that fits the calisthenics lifestyle.

Progress doesn’t require suffering.

Progress requires repetition that the body can actually recover from.

A rope and a little patience can get you a lot of that, without turning training into a second full-time job.

If the goal is being strong, capable, and still able to walk down stairs like a normal human, rope is a surprisingly good ally.