One of the weirdest things about calisthenics is that progress can stop without ever feeling like it stopped.

You’re still training regularly.

You’re still sweating.

You’re still doing movements that look solid.

From the outside, everything seems fine.

But weeks pass, then months, and the progression you care about is exactly where it was before.

Not worse.

Not better.

Just… stuck.

This kind of stall is frustrating precisely because it doesn’t announce itself.

There’s no dramatic failure, no obvious mistake, no single session where things fall apart.

It just quietly settles in.

And no, this usually has nothing to do with motivation, discipline, or “wanting it badly enough.”

Most calisthenics stalls come from how progressions actually work versus how we think they work.

Calisthenics is not just strength.

It’s strength, skill, coordination, joint tolerance, and how well your weekly training choices line up with the goal.

This article is about spotting those silent stalls early and fixing them in a practical, non-guru way.

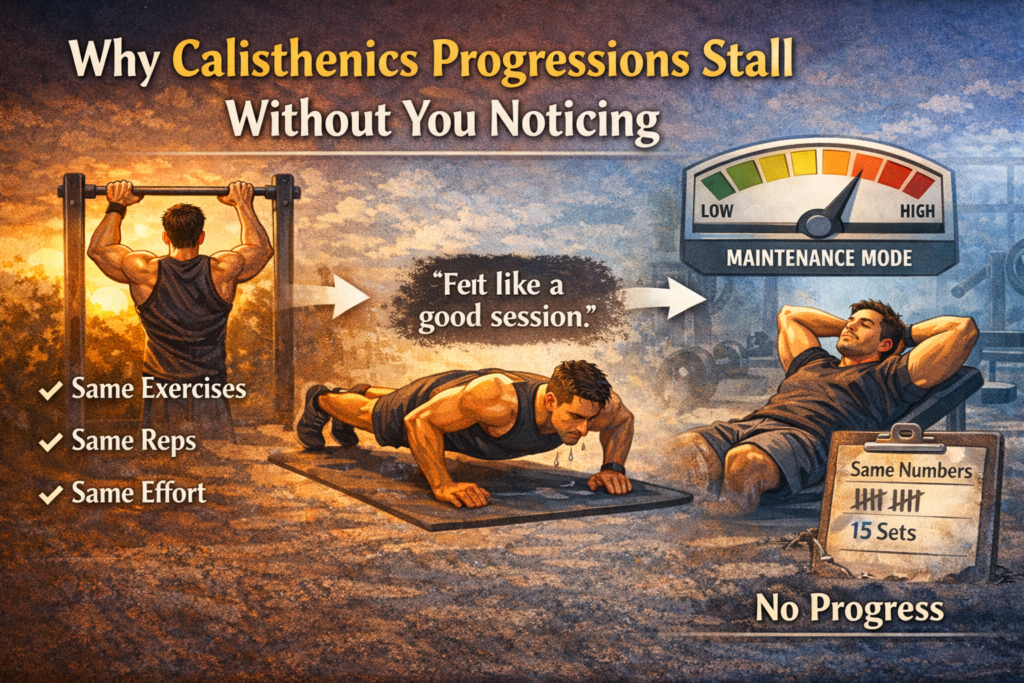

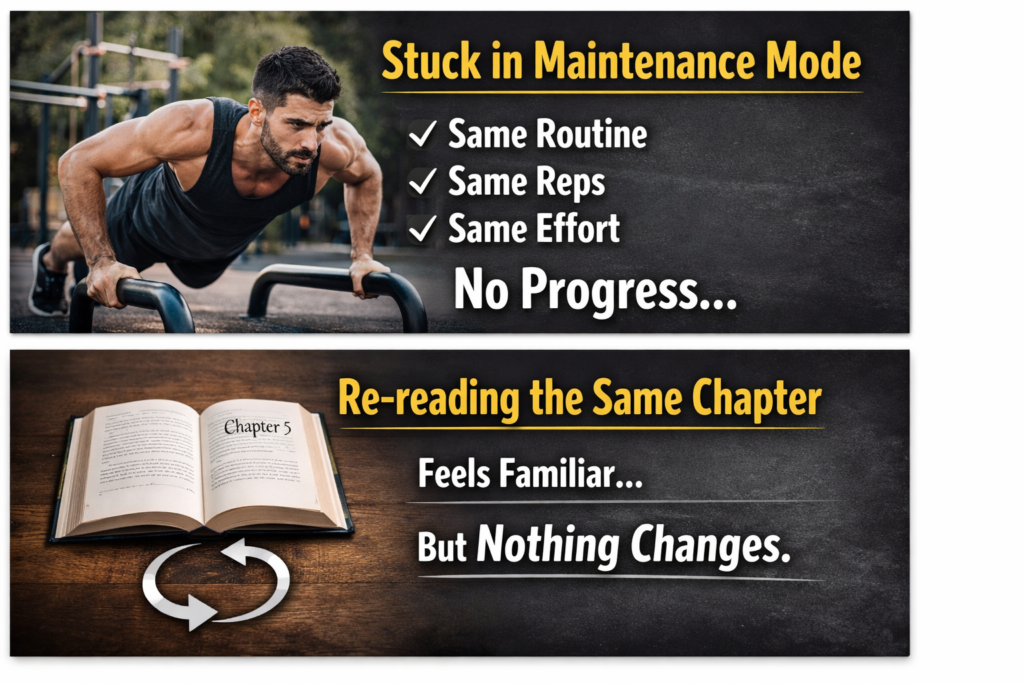

The most common stall: training that turns into maintenance

A huge number of calisthenics routines slowly drift into maintenance without people realizing it.

Maintenance isn’t bad.

Sometimes it’s exactly what you want.

The problem is thinking you’re progressing when the workout is only good enough to keep what you already have.

Here’s how it usually happens.

You repeat the same “solid” session every week.

Same exercises.

Same reps.

Same rest times.

Same effort level.

The workout feels productive, familiar, and comfortable.

Your body adapts to it… and then stops needing to adapt.

Because nothing new is being asked of it anymore.

It’s like rereading the same chapter of a book and expecting the story to advance.

The chapter is still good.

It’s just not new.

Calisthenics progressions move when training sends a clear signal that something needs to change.

Not an extreme signal.

Just a consistent one.

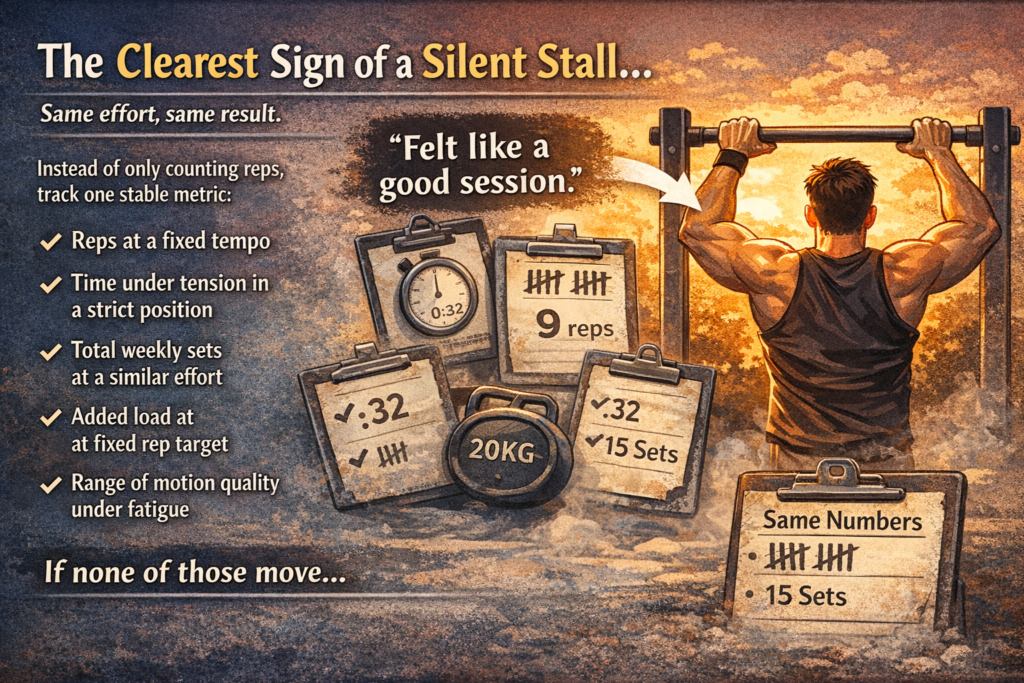

The clearest sign of a silent stall

One of the most reliable stall signals is simple:

same effort, same result.

You test the same progression.

It feels just as hard.

It looks just as hard.

Recovery feels the same.

Numbers don’t change.

Yet it still “felt like a good session.”

Feeling good is great.

Feeling good while staying stuck is extremely common.

Instead of only counting reps, track one stable metric:

- Reps at a fixed tempo

- Time under tension in a strict position

- Total weekly sets at a similar effort

- Added load at a fixed rep target

- Range of motion quality under fatigue

If none of those move for 4–6 weeks, you’re not “almost there.”

You’re parked.

And parking is fixable once you know why it’s happening.

Stall type 1: practicing without building

Calisthenics requires practice.

Practice is specific, frequent, and technical.

Strength building is different.

It requires enough load and volume to force adaptation.

It’s not always pretty.

Many people do plenty of practice but very little actual building.

They perform a few clean sets close to their limit and stop there.

That maintains skill and coordination, but it doesn’t always build the raw strength needed for the next progression.

Most long-term progress comes from running two lanes at the same time:

- A skill lane for the exact movement

- A building lane for the muscles and positions holding you back

Skipping the building lane is like trying to learn a language only by speaking and never studying vocabulary.

You’ll improve, but much more slowly than you could.

The building work is often boring.

Rows, dips, split squats, hamstring work, scapular control drills.

They’re not flashy, but they’re the reason the flashy skills eventually happen.

Stall type 2: “easy” sets that are too easy

Submaximal training is smart and sustainable.

But only if it’s actually challenging enough to matter.

If you finish a set and could immediately repeat it with perfect form, the stimulus is probably too low.

Not always, but often.

For most calisthenics movements, leaving 1–3 reps in reserve on working sets is a productive range.

That’s not a rule carved in stone, just a practical guideline.

When everything stays 6–8 reps away from failure, progressions tend to stall quietly.

The body simply isn’t being asked to adapt.

Stall type 3: always tired, never overloaded

This one feels confusing.

Training feels hard, recovery feels slow, yet nothing improves.

The issue is usually not effort, but clarity.

Fatigue often comes from:

- Too much overlapping volume

- Too many medium-hard days

- Short rest times that reduce quality

- Too much variety, not enough focus

It’s like running twenty apps at once and wondering why the system slows down.

Progressions respond better to fewer exercises done with clearer intent and better recovery between quality sets.

Sometimes removing work moves things forward faster than adding more.

Stall type 4: missing rungs in the progression

Some calisthenics progressions are simply too big of a jump.

Going from solid pull-ups straight to archer pull-ups, for example, changes grip, leverage, stability, and scapular demands all at once.

If the gap is too large, you end up “being patient” while nothing actually changes.

Better rungs include:

- Assisted variations with controlled assistance

- Eccentrics with strict positioning

- Isometric holds at the sticking point

- Partial reps that target the hardest range

- Tempo-controlled reps

Talent helps, but smart stepping stones help more.

Stall type 5: form improves by avoiding the hard part

Sometimes technique “improves” by quietly skipping the weakest position.

Push-ups shorten the range.

Pull-ups lose the last inch at the top.

Dips stop going deep.

Everything feels smoother, but the progression doesn’t move.

That’s because the hardest position is usually the one that builds the next step.

An honest range of motion isn’t about purity.

It’s about physics.

The next progression demands strength where you’re currently avoiding work.

Filming one set from the side and choosing a single non-negotiable checkpoint can be eye-opening.

Reps may drop at first.

That’s normal.

Now you’re training the real version again.

Stall type 6: connective tissue is the limiter

Muscles adapt relatively fast.

Tendons, joints, and connective tissue adapt more slowly.

You might feel strong enough, but your elbows, wrists, or shoulders aren’t fully tolerant yet.

So you unconsciously hold back.

This kind of stall looks like caution, not injury.

Caution is smart.

Ignoring tissue adaptation isn’t.

Gradual loading, isometrics, controlled tempo work, longer warm-ups, and planned deloads all help here.

They’re not exciting, but they keep progress sustainable.

Stall type 7: testing instead of training

Testing progressions is fun.

Doing it too often is expensive.

Trying the hardest version every week creates fatigue without enough quality volume to improve it.

Training should focus on:

- Submaximal skill practice

- Builder work for the limiting factors

- Infrequent, intentional testing

Testing every week is like running benchmarks without optimizing anything.

The numbers don’t change, and everything just gets tired.

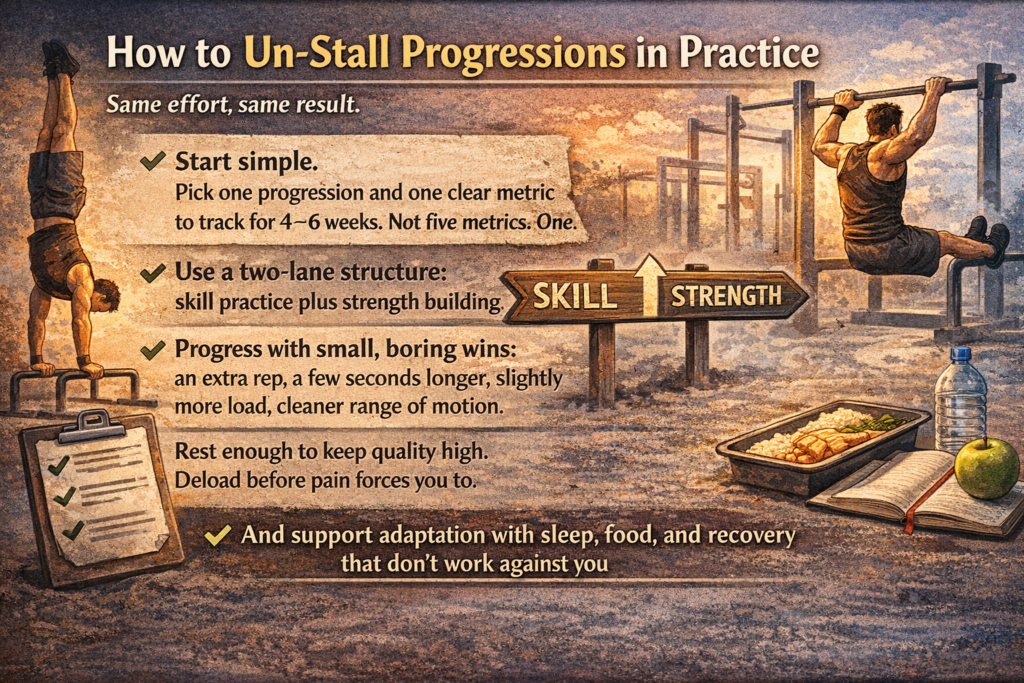

How to un-stall progressions in practice

Start simple.

Pick one progression and one clear metric to track for 4–6 weeks.

Not five metrics.

One.

Use a two-lane structure:

skill practice plus strength building.

Progress with small, boring wins:

an extra rep, a few seconds longer, slightly more load, cleaner range of motion.

Rest enough to keep quality high.

Deload before pain forces you to.

And support adaptation with sleep, food, and recovery that don’t work against your goals.

Practical examples to actually move progressions again

Below are real, simple examples of how people usually break a stall in calisthenics, without reinventing their entire training plan.

Example 1: Pull-up progression that feels stuck

Problem:

Pull-ups feel smooth, form looks great, but reps or difficulty never increase.

Common mistake:

Only repeating clean bodyweight pull-ups.

Practical fix:

Use a builder + skill combo.

- Skill lane:

6–8 sets of clean pull-ups, stopping 2 reps before failure. - Builder lane (pick one):

- Weighted pull-ups for low reps

- Slow eccentrics (5–7 seconds down)

- Top-position isometric holds

Why it works:

The skill stays sharp, but strength is finally forced to adapt.

Example 2: Dips or push-ups that never get harder

Problem:

You can do a lot of reps, but harder variations feel impossible.

Common mistake:

Living in high-rep comfort zones.

Practical fix:

Increase difficulty without changing the movement.

- Add load with a belt or backpack

- Use tempo (3–4 seconds down)

- Increase depth while keeping form strict

Why it works:

The stimulus changes without abandoning the pattern your body already knows.

Example 3: Stuck before advanced skills (front lever, planche, OAP)

Problem:

You practice the skill often, but it never feels more achievable.

Common mistake:

Testing the hardest version too frequently.

Practical fix:

Train the weakest position directly.

- Isometric holds at the hardest angle you can control

- Partial reps through the sticking range

- Assisted variations with consistent assistance

Why it works:

You stop “hoping” the skill shows up and start strengthening the exact limit.

Example 4: Always tired, progress still frozen

Problem:

Training feels hard, joints feel busy, progress doesn’t move.

Common mistake:

Too much volume spread everywhere.

Practical fix:

Reduce, then focus.

- Cut total exercises by 20–30%

- Rest longer between hard sets

- Keep only movements that support the main goal

Why it works:

Recovery improves, quality goes up, and adaptation finally has space to happen.

Example 5: Progress stalls even though consistency is perfect

Problem:

You never miss workouts, but results don’t match effort.

Common mistake:

Confusing consistency with progression.

Practical fix:

Track one variable for 4 weeks.

- Total reps at the same difficulty

- Hold time in a strict position

- Load used for a fixed rep target

If that number doesn’t move, neither will the progression.

Why it works:

Progress becomes measurable instead of emotional.

The simple rule that ties everything together

If a progression hasn’t moved in 4–6 weeks, one of these is missing:

- Enough overload

- Enough recovery

- Small enough progression steps

Fixing one of those is usually enough to restart progress.

Not all three.

Not a full program rewrite.

Just one clear adjustment, applied calmly.

The mindset that keeps progress moving

Stalls feel personal because calisthenics is personal.

It’s you versus gravity.

But a stall is just feedback.

Not a verdict on your genetics or your work ethic.

People who get good at calisthenics aren’t magic.

They just learn to notice stalls earlier and adjust calmly instead of panicking.

Keep the signal clear.

Build the missing rungs.

Recover like adaptation actually matters.

Progressions rarely explode forward.

They stack quietly, then show up one day when you least expect it.

You’re not behind.

You’re just working on the part that makes the next step inevitable.